| This article should specify the language of its non-English content, using {{lang}}, {{transliteration}} for transliterated languages, and {{IPA}} for phonetic transcriptions, with an appropriate ISO 639 code. Misplaced Pages's multilingual support templates may also be used. See why. (May 2019) |

| Tatar | |

|---|---|

| татар теле tatar tele تاتار تئلئ • تاتار تلی | |

Tatar in Cyrillic, Latin, and Perso-Arabic scripts Tatar in Cyrillic, Latin, and Perso-Arabic scripts | |

| Region | Northern Eurasia |

| Ethnicity | Tatars |

| Speakers | L1: 4 million (2020) L2: 810,000 (2020) |

| Language family | Turkic

|

| Early form | Old Tatar language |

| Dialects |

|

| Writing system | Tatar alphabet (Cyrillic, Latin, formerly Arabic) |

| Official status | |

| Official language in | Tatarstan (Russia) |

| Recognised minority language in | China Poland |

| Regulated by | Institute of Language, Literature and Arts of the Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Tatarstan |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | tt |

| ISO 639-2 | tat |

| ISO 639-3 | tat |

| Glottolog | tata1255 |

| Linguasphere | 44-AAB-be |

| |

Tatar is classified as Vulnerable by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger Tatar is classified as Vulnerable by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | |

| This article contains IPA phonetic symbols. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Unicode characters. For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. | |

Tatar (/ˈtɑːtər/ TAH-tər; татар теле, tatar tele or татарча, tatarça) is a Turkic language spoken by the Volga Tatars mainly located in modern Tatarstan (European Russia), as well as Siberia and Crimea.

Geographic distribution

The Tatar language is spoken in Russia by about 5.3 million people, and also by communities in Azerbaijan, China, Finland, Georgia, Israel, Kazakhstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Turkey, Ukraine, the US, Uzbekistan, and several other countries. Globally, there are more than 7 million speakers of Tatar.

Tatar is also the mother tongue for several thousand Mari, a Finnic people; Mordva's Qaratay group also speak a variant of Kazan Tatar.

In the 2010 census, 69% of Russian Tatars claimed at least some knowledge of the Tatar language. In Tatarstan, 93% of Tatars and 3.6% of Russians claimed to have at least some knowledge of the Tatar language. In neighbouring Bashkortostan, 67% of Tatars, 27% of Bashkirs, and 1.3% of Russians claimed to understand basic Tatar language.

Official status

Tatar, along with Russian, is the official language of the Republic of Tatarstan. The official script of Tatar language is based on the Cyrillic script with some additional letters. The Republic of Tatarstan passed a law in 1999, which came into force in 2001, establishing an official Tatar Latin alphabet. A Russian federal law overrode it in 2002, making Cyrillic the sole official script in Tatarstan since. Unofficially, other scripts are used as well, mostly Latin and Arabic. All official sources in Tatarstan must use Cyrillic on their websites and in publishing. In other cases, where Tatar has no official status, the use of a specific alphabet depends on the preference of the author.

The Tatar language was made a de facto official language in Russia in 1917, but only within the Tatar Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. Tatar is also considered to have been the official language in the short-lived Idel-Ural State, briefly formed during the Russian Civil War.

The usage of Tatar declined during the 20th century. By the 1980s, the study and teaching of Tatar in the public education system was limited to rural schools. However, Tatar-speaking pupils had little chance of entering university because higher education was available in Russian almost exclusively.

As of 2001, Tatar was considered a potentially endangered language while Siberian Tatar received "endangered" and "seriously endangered" statuses, respectively. Higher education in Tatar can only be found in Tatarstan, and is restricted to the humanities. In other regions Tatar is primarily a spoken language and the number of speakers as well as their proficiency tends to decrease. Tatar is popular as a written language only in Tatar-speaking areas where schools with Tatar language lessons are situated. On the other hand, Tatar is the only language in use in rural districts of Tatarstan.

Since 2017, Tatar language classes are no longer mandatory in the schools of Tatarstan. According to the opponents of this change, it will further endanger the Tatar language and is a violation of the Tatarstan Constitution which stipulates the equality of Russian and Tatar languages in the republic.

Dialects

There are two main dialects of Tatar:

- Central or Middle (Kazan)

- Western (Mişär or Mishar)

All of these dialects also have subdivisions. Significant contributions to the study of the Tatar language and its dialects, were made by a scientist Gabdulkhay Akhatov, who is considered to be the founder of the modern Tatar dialectological school.

Spoken idioms of Siberian Tatars, which differ significantly from the above two, are often considered as the third dialect group of Tatar by some, but as an independent language on its own by others.

Central or Middle

The Central or Middle dialectal group is spoken in Kazan and most of Tatarstan and is the basis of the standard literary Tatar language. Middle Tatar includes the Nagaibak dialect.

Mishar

Main article: Mishar Tatar dialectThe Western (Mişär) dialect is distinguished from the Central dialect especially by the absence of the uvular q and ğ and the rounded å of the first syllable. Letters ç and c are pronounced as affricates. Regional differences exist also.

Mishar is the dialect spoken by the Tatar minority of Finland.

Siberian Tatar

Main article: Siberian Tatar languageTwo main isoglosses that characterize Siberian Tatar are ç as [ts] and c as [j], corresponding to standard [ɕ] and [ʑ]. There are also grammatical differences within the dialect, scattered across Siberia.

Many linguists claim the origins of Siberian Tatar dialects are actually independent of Volga–Ural Tatar; these dialects are quite remote both from Standard Tatar and from each other, often preventing mutual comprehension. The claim that this language is part of the modern Tatar language is typically supported by linguists in Kazan, Moscow and by Siberian Tatar linguists and denounced by some Russian and Tatar ethnographs.

Over time, some of these dialects were given distinct names and recognized as separate languages (e.g. the Chulym language) after detailed linguistic study. However, the Chulym language was never classified as a dialect of Tatar language. Confusion arose because of the endoethnonym "Tatars" used by the Chulyms. The question of classifying the Chulym language as a dialect of the Khakass language was debatable. A brief linguistic analysis shows that many of these dialects exhibit features which are quite different from the Volga–Ural Tatar varieties, and should be classified as Turkic varieties belonging to several sub-groups of the Turkic languages, distinct from Kipchak languages to which Volga–Ural Tatar belongs.

Phonology

Vowels

There exist several interpretations of the Tatar vowel phonemic inventory. In total Tatar has nine or ten native vowels, and three or four loaned vowels (mainly in Russian loanwords).

According to Baskakov (1988) Tatar has only two vowel heights, high and low. There are two low vowels, front and back, while there are eight high vowels: front and back, round (R+) and unround (R−), normal and short (or reduced).

| Front | Back | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R− | R+ | R− | R+ | ||

| High | Normal | i | ü | ï | u |

| Short | e | ö | ë | o | |

| Low | ä | a | |||

Poppe (1963) proposed a similar yet slightly different scheme with a third, higher mid, height, and with nine vowels.

| Front | Back | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R− | R+ | R− | R+ | |

| High | i | ü | u | |

| Higher Mid | e | ö | ï | o |

| Low | ä | a | ||

According to Makhmutova (1969) Tatar has three vowel heights: high, mid and low, and four tongue positions: front, front-central, back-central and back (as they are named when cited).

| Front | Central | Back | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Front | Back | |||||||

| R− | R+ | R− | R+ | R− | R+ | R− | R+ | |

| High | i | ü | ï | u | ||||

| Mid | e | ö | ë | o | ||||

| Low | ä | a | ||||||

The mid back unrounded vowel ''ë is usually transcribed as ı, though it differs from the corresponding Turkish vowel.

The tenth vowel ï is realized as the diphthong ëy (IPA: [ɯɪ]), which only occurs word-finally, but it has been argued to be an independent phoneme.

Phonetically, the native vowels are approximately thus (with the Cyrillic letters and the usual Latin romanization in angle brackets):

| Front | Back | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R− | R+ | R− | R+ | |

| High | и ⟨i⟩ [i] |

ү ⟨ü⟩ |

ый ⟨ıy⟩ |

у ⟨u⟩ [u] |

| Mid | э, е ⟨e⟩ |

ө ⟨ö⟩ |

ы ⟨ı⟩ |

о ⟨o⟩ [ŏ] |

| Low | ә ⟨ä⟩ |

а ⟨a⟩ [ɑ] |

||

In polysyllabic words, the front-back distinction is lost in reduced vowels: all become mid-central. The mid reduced vowels in an unstressed position are frequently elided, as in кеше keşe > 'person', or кышы qışı > '(his) winter'. Low back /ɑ/ is rounded [ɒ] in the first syllable and after [ɒ], but not in the last, as in бала bala 'child', балаларга balalarğa 'to children'. In Russian loans there are also [ɨ], [ɛ], [ɔ], and [ä], written the same as the native vowels: ы, е/э, о, а respectively.

Historical shifts

Historically, the Old Turkic mid vowels have raised from mid to high, whereas the Old Turkic high vowels have become the Tatar reduced mid series. (The same shifts have also happened in Bashkir.)

| Vowel | Old Turkic | Kazakh | Tatar | Bashkir | Gloss |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *e | *et | et | it | it | 'meat' |

| *ö | *söz | söz | süz | hüź [hyθ] | 'word' |

| *o | *sol | sol | sul | hul | 'left' |

| *i | *it | it | et | et | 'dog' |

| *ï | *qïz | qız | qëz [qɤ̆z] | qëź [qɤ̆θ] | 'girl' |

| *u | *qum | qum | qom | qom | 'sand' |

| *ü | *kül | kül | köl | köl | 'ash' |

Consonants

| Labial | Dental | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasals | м ⟨m⟩ /m/ |

н ⟨n⟩ /n/ |

ң ⟨ñ⟩ /ŋ/ |

|||||

| Plosives | Voiceless | п ⟨p⟩ /p/ |

т ⟨t⟩ /t/ |

к ⟨k⟩ /k/ |

къ ⟨q⟩ /q/ |

э/ь ⟨ʼ⟩ /ʔ/ | ||

| Voiced | б ⟨b⟩ /b/ |

д ⟨d⟩ /d/ |

г ⟨g⟩ /ɡ/ |

|||||

| Affricates | Voiceless | ц ⟨ts⟩ /ts/ |

ч ⟨ç⟩ /tɕ/ |

|||||

| Voiced | җ ⟨c⟩ /dʑ/ |

|||||||

| Fricatives | Voiceless | ф ⟨f⟩ /f/ |

с ⟨s⟩ /s/ |

ш ⟨ş⟩ /ʃ/ |

ч ⟨ś⟩ /ɕ/ |

х ⟨x⟩ /χ/ |

һ ⟨h⟩ /h/ | |

| Voiced | в ⟨v⟩ /v/ |

з ⟨z⟩ /z/ |

ж ⟨j⟩ /ʒ/ |

җ ⟨ź⟩ /ʑ/ |

гъ ⟨ğ⟩ /ʁ/ |

|||

| Trill | р ⟨r⟩ /r/ |

|||||||

| Approximants | л ⟨l⟩ /l/ |

й ⟨y⟩ /j/ |

у/ү/в ⟨w⟩ /w/ |

|||||

- Notes

- ^* The phonemes /v/, /ts/, /tɕ/, /ʒ/, /h/, /ʔ/ are only found in loanwords. /f/ occurs more commonly in loanwords, but is also found in native words, e.g. yafraq 'leaf'. /v/, /ts/, /tɕ/, /ʒ/ may be substituted with the corresponding native consonants /w/, /s/, /ɕ/, /ʑ/ by some Tatars.

- ^† /dʑ/ and /tɕ/ are the dialectal Western (Mişär) pronunciations of җ ⟨c⟩ /ʑ/ and ч ⟨ç⟩ /ɕ/, the latter are in the literary standard and in the Central (Kazan) dialect. /ts/ is the variant of ч ⟨ç⟩ /ɕ/ as pronounced in the Eastern (Siberian) dialects and some Western (Mişär) dialects. Both /tɕ/ and /ts/ are also used in Russian loanwords (the latter written ц).

- ^‡ /q/ and /ʁ/ are usually considered allophones of /k/ and /ɡ/ in the environment of back vowels, so they are never written in the Tatar Cyrillic orthography in native words, and only rarely in loanwords with къ and гъ. However, /q/ and /ʁ/ also appear before front /æ/ in Perso-Arabic loanwords which may indicate the phonemic status of these uvular consonants.

Palatalization

Tatar consonants usually undergo slight palatalization before front vowels. However, this allophony is not significant and does not constitute a phonemic status. This differs from Russian where palatalized consonants are not allophones but phonemes on their own. There are a number of Russian loanwords which have palatalized consonants in Russian and are thus written the same in Tatar (often with the "soft sign" ь). The Tatar standard pronunciation also requires palatalization in such loanwords; however, some Tatar may pronounce them non-palatalized.

Syllables

In native words there are six types of syllables (Consonant, Vowel, Sonorant):

- V (ı-lıs, u-ra, ö-rä)

- VC (at-law, el-geç, ir-kä)

- CV (qa-la, ki-ä, su-la)

- CVC (bar-sa, sız-law, köç-le, qoş-çıq)

- VSC (ant-lar, äyt-te, ilt-kän)

- CVSC (tört-te, qart-lar, qayt-qan)

Loanwords allow other types: CSV (gra-mota), CSVC (käs-trül), etc.

Prosody

Stress is usually on the final syllable. However, some suffixes cannot be stressed, so the stress shifts to the syllable before that suffix, even if the stressed syllable is the third or fourth from the end. A number of Tatar words and grammatical forms have the natural stress on the first syllable. Loanwords, mainly from Russian, usually preserve their original stress (unless the original stress is on the last syllable, in such a case the stress in Tatar shifts to suffixes as usual, e.g. sovét > sovetlár > sovetlarğá).

Phonetic alterations

Tatar phonotactics dictate many pronunciation changes which are not reflected in the orthography.

- Unrounded vowels ı and e become rounded after o or ö:

- коры/qorı >

- борын/borın >

- көзге/közge >

- соры/sorı >

- Nasals are assimilated to the following stops:

- унбер/unber >

- менгеч/mengeç >

- Stops are assimilated to the preceding nasals (this is reflected in writing):

- урманнар/urmannar ( < urman + lar)

- комнар/komnar ( < kom + lar)

- Voicing may also undergo assimilation:

- күзсез/küzsez >

- Unstressed vowels may be syncopated or reduced:

- урыны/urını>

- килене/kilene >

- Vowels may also be elided:

- кара урман/qara urman >

- килә иде/kilä ide >

- туры урам/turı uram >

- була алмыйм/bula almıym >

- In consonant clusters longer than two phones, ı or e (whichever is dictated by vowel harmony) is inserted into speech as an epenthetic vowel.

- банк/bank >

- Final consonant clusters are simplified:

- артист/artist >

- Final devoicing is also frequent:

- табиб/tabib >

Grammar

Like other Turkic languages, Tatar is an agglutinative language.

Nouns

Tatar nouns are inflected for cases and numbers. Case suffixes change depending on the last consonants of the noun, while nouns ending in п/к are voiced to б/г (китабым) when a possessive suffix was added. Suffixes below are in back vowel, with front variant can be seen at #Phonology section.

| Case | After voiced consonants | After nasals | After unvoiced consonants | Special endings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative (баш килеш) | – | |||

| Accusative (төшем килеше) | -ны -nı | -н -n | ||

| Genitive (иялек килеше) | -ның -nıñ | |||

| Dative (юнәлеш килеше) | -га -ğa | -ка -qa | -а, -на -a, -na | |

| Locative (урын-вакыт килеше) | -да -da | -та -ta | -нда -nda | |

| Ablative (чыгыш килеше) | -дан -dan | -нан -nan | -тан -tan | -ннан -nnan |

| Plural | ||||

| Nominative | -лар -lar | -нар -nar | -лар -lar | |

| Accusative | -ларны -larnı | -нарны -narnı | -ларны -larnı | |

| Genitive | -ларның -larnıñ | -нарның -narnıñ | -ларның -larnıñ | |

| Dative | -ларга -larğa | -нарга -narğa | -ларга -larğa | |

| Locative | -ларда -larda | -нарда -narda | -ларда -larda | |

| Ablative | -лардан -lardan | -нардан -nardan | -лардан -lardan | |

The declension of possessive suffixes is even more irregular, with the dative suffix -а used in 1st singular and 2nd singular suffixes, and the accusative, dative, locative, and ablative endings -н, -на, -нда, -ннан is used after 3rd person possessive suffix. Nouns ending in -и, -у, or -ү, although phonologically vowels, take consonantic endings.

| Person | After consonants | After vowels |

|---|---|---|

| 1st singular | -ым -ım | -м -m |

| 2nd singular | -ың -ıñ | -ң -ñ |

| 3rd | -ы -ı | -сы -sı |

| 1st plural | -ыбыз -ıbız | -быз -bız |

| 2nd plural | -ыгыз -ığız | -гыз -ğız |

Declension of pronouns

The declension of personal and demonstrative pronouns tends to be irregular. Irregular forms are in bold.

| Case | Singular | Plural | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | you (sg.), thou | he, she, it | we | you (pl.) | they | |

| Nominative | мин min | син sin | ул ul | без bez | сез sez | алар alar |

| Accusative | мине mine | сине sine | аны anı | безне bezne | сезне sezne | аларны alarnı |

| Genitive | минем minem | синең sineñ | аның anıñ | безнең bezneñ | сезнең sezneñ | аларның alarnıñ |

| Dative | миңа miña | сиңа siña | аңа aña | безгә bezgä | сезгә sezgä | аларга alarğa |

| Locative | миндә mindä | синдә sindä | анда anda | бездә bezdä | сездә sezdä | аларда alarda |

| Ablative | миннән minnän | синнән sinnän | аннан annan | бездән bezdän | сездән sezdän | алардан alardan |

| Case | Singular | Plural | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| "This" | "That" | "These" | "Those" | |

| Nominative | бу bu | шул şul | болар bolar | шулар şular |

| Accusative | моны monı | шуны şunı | боларны bolarnı | шуларны şularnı |

| Genitive | моның monıñ | шуның şunıñ | боларның bolarnıñ | шуларның şularnıñ |

| Dative | моңа moña | шуңа şuña | боларга bolarğa | шуларга şularğa |

| Locative | монда monda | шунда şunda | боларда bolarda | шуларда şularda |

| Ablative | моннан monnan | шуннан şunnan | болардан bolardan | шулардан şulardan |

| Case | Who? | What? |

|---|---|---|

| Nominative | кем kem | нәрсә närsä |

| Accusative | кемне kemne | нәрсәне närsäne |

| Genitive | кемнең kemneñ | нәрсәнең närsäneñ |

| Dative | кемгә kemgä | нәрсәгә närsägä |

| Locative | кемдә kemdä | нәрсәдә närsädä |

| Ablative | кемнән kemnän | нәрсәдән närsädän |

Verbs

| Tense | After voiced consonants | After unvoiced consonants | After vowels |

|---|---|---|---|

| Present | -а -a | -ый -ıy | |

| Definite past | -ды -dı | -ты -tı | -ды -dı |

| Indefinite past | -ган -ğan | -кан -qan | -ган -ğan |

| Definite future | -ачак -açaq | -ячак -yaçaq | |

| Indefinite future | -ар/ыр -ar/-ır | -р -r | |

| Conditional | -са -sa | ||

| Non-finite tenses | |||

| Present participle | -учы -uçı | ||

| Past participle | -ган -ğan | -кан -qan | -ган -ğan |

| Future participle | -асы -ası | -ыйсы -ıysı | |

| Definite future participle | -ачак -açaq | ||

| Indefinite future participle | -ар/-ыр -ar/ır | -р -r | |

| Verbal participle | -ып -ıp | -п -p | |

| Pre-action gerund | -ганчы -ğançı | -канчы -qançı | -ганчы -ğançı |

| Post-action gerund | -гач -ğaç | -кач -qaç | -гач -ğaç |

| Verbal noun | -у | ||

| Infinitive | -мак -maq | ||

| -арга/-ырга -arğa/ırğa | -рга -rğa | ||

The distribution of present tense suffixes is complicated, with the former (also with vowel harmony) is used with verb stems ending in consonants, and the latter is used with verb stem ending in vowels (with the last vowel being deleted, эшләү – эшли, compare Turkish işlemek – continuous işliyor). The distribution of indefinite future tense is more complicated in consonant-ending stems, it is resolved by -арга/-ырга infinitives (язарга – язар). However, because some have verb citation forms in verbal noun (-у), this rule becomes somewhat unpredictable.

Tenses are negated with -ма, however in the indefinite future tense and the verbal participle they become -мас and -мыйча instead, respectively. Alongside vowel-ending stems, the suffix also becomes -мый when negates the present tense. To form interrogatives, the suffix -мы is used.

| Type | 1st singular | 2nd singular | 3rd singular | 1st plural | 2nd plural | 3rd plural |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | -мын/-м -mın/-m | -сың -sıñ | -∅ | -быз -bız | -сыз -sız | -лар/-нар -lar/-nar |

| II | -м -m | -ң -ñ | -∅ | -к -q, -k | -гыз -ğız | -лар/-нар -lar/-nar |

| Imperative | -ыйм -ıym | -∅ | -сын -sın | -ыйк -ıyq | -(ы)гыз -ığız | -сыннар -sınnar |

Definite past and conditional tenses use type II personal inflections instead. When in the case of present tense, short ending (-м) is used. After vowels, the first person imperative forms deletes the last vowel, similar to the present tense does (эшләү – эшлим). Like plurals of nouns, the suffix -лар change depending the preceding consonants (-алар, but -ганнар).

Anomalous verbs

Some verbs, however, fall into this category. Dozens of them have irregular stems with a final mid vowel, but obscured on the infinitive (уку – укы, укый, төзү – төзе, төзи). The verbs кору "to build", тану "to disclaim", ташу "to spill" have contrastive meanings with verbs with their final vowelled counterparts, meaning "to dry", "to know", "to carry".

The verb дию "to say" is significantly more irregular than any other verbs: its 2nd person singular imperative is диген, while its expected regular form is repurposed as the present tense forms (дим, диң, ди...).

Predicatives

| After voiced consonants | After unvoiced consonants | |

|---|---|---|

| 1st singular | -мын -mın | |

| 2nd singular | -сың -sıñ | |

| 3rd | -дыр -dır | -тыр -tır |

| 1st plural | -быз -bız | |

| 2nd plural | -сыз -sız | |

These predicative suffixes have now fallen into disuse, or rarely used.

Writing system

Main articles: Tatar alphabet and Jaꞑalif

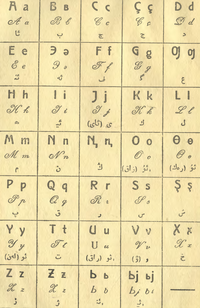

During its history, Tatar has been written in Arabic, Latin and Cyrillic scripts.

Before 1928, Tatar was mostly written in Arabic script (Иске имля/İske imlâ, "Old orthography", to 1920; Яңа имла/Yaña imlâ, "New orthography", 1920–1928).

During the 19th century, Russian Christian missionary Nikolay Ilminsky devised the first Cyrillic alphabet for Tatar. This alphabet is still used by Christian Tatars (Kryashens).

In the Soviet Union after 1928, Tatar was written with a Latin alphabet called Jaꞑalif.

In 1939, in Tatarstan and all other parts of the Soviet Union, a Cyrillic script was adopted and is still used to write Tatar. It is also used in Kazakhstan.

The Republic of Tatarstan passed a law in 1999 that came into force in 2001 establishing an official Tatar Latin alphabet. A Russian federal law overrode it in 2002, making Cyrillic the sole official script in Tatarstan since. In 2004, an attempt to introduce a Latin-based alphabet for Tatar was further abandoned when the Constitutional Court ruled that the federal law of 15 November 2002 mandating the use of Cyrillic for the state languages of the republics of the Russian Federation does not contradict the Russian constitution. In accordance with this Constitutional Court ruling, on 28 December 2004, the Tatar Supreme Court overturned the Tatarstani law that made the Latin alphabet official.

In 2012 the Tatarstan government adopted a new Latin alphabet but with limited usage (mostly for Romanization).

- Tatar Perso-Arabic alphabet (before 1928):

| آ | ا | ب | پ | ت | ث | ج | چ |

| ح | خ | د | ذ | ر | ز | ژ | س |

| ش | ص | ض | ط | ظ | ع | غ | ف |

| ق | ك | گ | نك | ل | م | ن | ه |

| و | ۇ | ڤ | ی | ئ |

- Tatar Old Latin (Jaꞑalif) alphabet (1928 to 1940):

| A a | B ʙ | C c | Ç ç | D d | E e | Ə ə | F f |

| G g | Ƣ ƣ | H h | I i | J j | K k | L l | M m |

| N n | Ꞑ ꞑ | O o | Ɵ ɵ | P p | Q q | R r | S s |

| Ş ş | T t | U u | V v | X x | У y | Z z | Ƶ ƶ |

| Ь ь | ' |

- Tatar Old Cyrillic alphabet (by Nikolay Ilminsky, 1861; the letters in parentheses are not used in modern publications):

| А а | Ӓ ӓ | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ё ё |

| Ж ж | З з | И и | (Іі) | Й й | К к | Л л | М м |

| Н н | Ҥ ҥ | О о | Ӧ ӧ | П п | Р р | С с | Т т |

| У у | Ӱ ӱ | Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Щ щ |

| Ъ ъ | Ы ы | Ь ь | (Ѣѣ) | Э э | Ю ю | Я я | (Ѳѳ) |

- Tatar Cyrillic alphabet (1939; the letter order adopted in 1997):

| А а | Ә ә | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ё ё |

| Ж ж | Җ җ | З з | И и | Й й | К к | Л л | М м |

| Н н | Ң ң | О о | Ө ө | П п | Р р | С с | Т т |

| У у | Ү ү | Ф ф | Х х | Һ һ | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш |

| Щ щ | Ъ ъ | Ы ы | Ь ь | Э э | Ю ю | Я я |

- 1999 Tatar Latin alphabet, made official by a law adopted by Tatarstani authorities but annulled by the Tatar Supreme Court in 2004:

| A a | Ə ə | B b | C c | Ç ç | D d | E e | F f |

| G g | Ğ ğ | H h | I ı | İ i | J j | K k | Q q |

| L l | M m | N n | Ꞑ ꞑ | O o | Ɵ ɵ | P p | R r |

| S s | Ş ş | T t | U u | Ü ü | V v | W w | X x |

| Y y | Z z | ʼ |

- 2012 Tatar Latin alphabet

| A a | Ä ä | B b | C c | Ç ç | D d | E e | F f |

| G g | Ğ ğ | H h | I ı | İ i | J j | K k | Q q |

| L l | M m | N n | Ñ ñ | O o | Ö ö | P p | R r |

| S s | Ş ş | T t | U u | Ü ü | V v | W w | X x |

| Y y | Z z | ʼ |

History

Main article: Turkic languages § Vocabulary comparisonTatar's ancestors are the extinct Bulgar and Kipchak languages.

The literary Tatar language is based on the Middle Tatar dialect and on the Old Tatar language (İske Tatar Tele). Both are members of the Volga-Ural subgroup of the Kipchak group of Turkic languages, although they also partly derive from the ancient Volga Bulgar language.

Most of the Uralic languages in the Volga River area have strongly influenced the Tatar language, as have the Arabic, Persian and Russian languages.

Crimean Tatar, although similar by name, belongs to another subgroup of the Kipchak languages. Unlike Kazan Tatar, Crimean Tatar is heavily influenced by Turkish (mostly its Ottoman variety with Arabic and Persian influences) and Nogai languages.

Examples

Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 1:

Барлык кешеләр дә азат һәм үз абруйлары һәм хокуклары ягыннан тиң булып туалар. Аларга акыл һәм вөҗдан бирелгән һәм бер-берсенә карата туганнарча мөнасәбәттә булырга тиешләр.

Barlıq keşelär dä azat häm üz abruyları häm xoquqları yağınnan tiñ bulıp tualar. Alarğa aqıl häm wöcdan birelgän häm ber-bersenä qarata tuğannarça mönasäbättä bulırğa tiyeşlär.

Tatar online learning

| This section contains promotional content. Please help improve it by removing promotional language and inappropriate external links, and by adding encyclopedic text written from a neutral point of view. (December 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

A common complaint among those curious about the Tatar language outside of Russia has been its lack of non-Russian Latin alphabet sources. For this, a young Germany-based Tatar architect Aygul Ahmetcan (Aygöl Əxmətcan), with the help of her partner, a linguistics student Bulat Shaymi (Bulat Şəymi), has created a Telegram channel Learn Tatar, which offers Tatar language teaching in English. It has gained thousands of viewers in few months after its creation in August 2023. Shaymi himself has a Youtube channel dedicated to Tatar content.

Since then, a website learntatar.com has also been established.

Among other helpful sources is the website Aybagar ("Sunflower"), which "publishes scientific works and original materials about Tatars, the Tatar language and Tatar culture, focusing especially on the Tatar diaspora worldwide". Tatar pronunciations can be found in Forvo and "Corpus of Written Tatar".

Modern Tatar Identity is a podcast that has "conversations with people who have dedicated a part of their life to Tatar and Tatar language research".

See also

References

- ^ Tatar at Ethnologue (27th ed., 2024)

- Ethnic Groups and Religious department, Fujian Provincial Government (13 September 2022). "少数民族的语言文字有哪些?". fujian.gov.cn (in Chinese). Retrieved 28 October 2022.

- "ACT of 6 January 2005 on national and ethnic minorities and on the regional languages" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 December 2019.

- "Tatar in Russian Federation | UNESCO WAL".

- "Tatar". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- Russian Census 2010. Владение языками населением (in Russian)

- Russian Census 2010. Владение языками населением наиболее многочисленных национальностей по субъектам Российской Федерации (in Russian)

- Wurm, S; Unesco (2001). Atlas of the world's languages in danger of disappearing. Paris: Unesco Pub. ISBN 978-92-3-103798-6.

- "Без языка: Казань отказалась от обязательных уроков татарского" (in Russian). BBC Russia. 1 December 2017.

- "Татарский язык становится "ящиком Пандоры"" (in Russian). БИЗНЕС Online. 22 September 2017.

- "Исмагил Хуснутдинов: "Под лозунгом добровольности татарский язык пытаются изгнать из школ"" (in Russian). БИЗНЕС Online. 12 November 2017.

- Jazyki Rossijskoi Federatsii i sosednih gosudarstv. Vol. 3. Moscow: Nauka. 2005. pp. 67–68. ISBN 5-02-011237-2.

- Zakiev, M. Z. (1997). "Tatar". In Tenišev, Ėdchjam R. (ed.). Tjurkskije jazyki. Jazyki mira. Moscow: Indrik. p. 371. ISBN 5-85759-061-2.

- Leitzinger, Antero (1996). Mishäärit – Suomen vanha islamilainen yhteisö. Helsinki: Kirja-Leitzinger. ISBN 952-9752-08-3.

- Information about Siberian Tatar

- Baskakov, Nikolai (1960). Санжеев, Г. Д. (ed.). Тюркские языки [Turkic languages]. Moscow, Russia: Издательство восточной литературы. p. 248.

- Утяшева, Гузель Чахваровна (2006). Русские заимствования в тоболо-иртышском диалекте сибирских татар [Russian borrowings in the Tobol-Irtysh dialect of the Siberian Tatars]. Tobolsk, Russia: Казанский федеральный университет. OCLC 1042797537.

- Рахимова, Роза Нуретдиновна (2007). Тюменский говор в системе диалектов сибирских татар: фонетико-морфологическая характеристика [Tyumen dialect in the system of dialects of the Siberian Tatars: phonetic and morphological characteristics]. Tyumen, Russia: Казанский федеральный университет. OCLC 1042799247.

- Рамазанова, Д. Б. (2006). "Сибирско-татарские диалекты и говоры татарского языка" [Materials of the IX All-Russian Scientific and Practical Conference "Suleiman Readings – 2006"] (PDF). Материалы IX Всероссийской научно-практической конференции "Сулеймановские чтения – 2006". Tyumen, Russia: Казанский федеральный университет. pp. 89–90.

- Валеев, Фоат Тач-Ахметович (1980). Западносибирские татары во второй половине XIX – начале XX в. (Историко-этнографические очерки) [West Siberian Tatars in the second half of the 19th to early 20th centuries. (Historical and ethnographic essays)]. Kazan', Tatarstan, Russia: Татарское книжное изд-во. OCLC 63230819.

- ^ Harrison, K. David; Kaun, Abigail R. (2003). "Vowels and Vowel Harmony in Namangan Tatar". In Holisky, Dee Ann; Tuite, Kevin (eds.). Current Trends in Caucasian, East European and Inner Asian Linguistics. John Benjamins. pp. 194–198. ISBN 9789027275257.

- ^ Berta, Árpád (1998). "Tatar and Bashkir". In Johanson, Lars; Csató, Éva Á. (eds.). The Turkic languages. Routledge. pp. 283–300.

- Johanson, Lars (1998). "The History of Turkic". In Johanson, Lars; Csató, Éva Á. (eds.). The Turkic languages. Routledge. p. 92.

- "Грамматика татарского языка". Archived from the original on 3 May 2020.

- ^ Burbiel, Gustav (2018). Tatar Grammar: А Grammar of the Contemporary Tatar Literary Language (PDF). Institute for Bible Translation. ISBN 978-5-93943-259-7.

- Зәкиев, М.З. (2016). Татар грамматикасы (PDF). Vol. 2 (2 ed.). Казан: ТӘһСИ. pp. 56–57.

- Spolsky, Bernard (2004). Language Policy. Cambridge University Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-521-01175-4.

- "Russia court sticks to letter law". BBC News. 16 November 2004. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ^ "The Tatar language will continue to be written through the Cyrillic alphabet". U.S. English Foundation. February 2005. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- "Law of the Republic of Tatarstan "On the use of the Tatar language as the state language of the Republic of Tatarstan" with an appendix (correspondence table)" (PDF).

- Tatar language – Princeton University Archived 13 December 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- (in Russian) Татарский язык в Интернете: информация о методах и средствах обучения

- "Булат Шаймиев: "Они пронесли эти знания сквозь века – неужели на мне все это и закончится?"". realnoyevremya. 2021.

- ""Learn Tatar" каналы авторы: "Татар телен төрле милләтләргә танытасым килә"". Азатлык Радиосы. February 2024.

- "Bulat Shaymi". Youtube.

- "Get to know the Tatar language and culture".

- "About – Aybagar". Aybagar.

- "Tatar pronunciation dictionary". Forvo.

- "Corpus of Written Tatar".

- "Modern Tatar Identity". Spotify.

Further reading

- Bukharaev, Ravilʹ; Matthews, D. J.; Matthews, David John (29 November 2023). Historical anthology of Kazan Tatar verse: voices of eternity. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-7007-1077-5.

- Gilmetdinova, Alsu; Malova, Irina (2018). "Language education for glocal interaction: English and Tatar". World Englishes. 37 (4): 624–634. doi:10.1111/weng.12324. S2CID 149975557.

- PEN (Organization). (1998). Tatar literature today. Kazan: Magarif Publishers.

- Poppe, N. N. (1963). Tatar manual: descriptive grammar and texts with a Tatar-English glossary. Bloomington: Indiana University.

- (in Russian) Ахатов Г. Х. Татарская диалектология (учебник для студентов вузов). – Казань, 1984.

- (in Russian) Татарская грамматика. В 3-х т. / Гл. ред. М. З. Закиев. – Казань, 1993.

External links

| Languages of Russia | |

|---|---|

| Federal language | |

| State languages of federal subjects | |

| Languages with official status | |

| Scripts | |

| In Russia, the Cyrillic alphabet is officially supported. For other, non-Cyrillic alphabets, separate federal laws are required. | |

| Languages of China | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Official | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Regional |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Indigenous |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Minority | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Varieties of Chinese | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Creole/Mixed | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Extinct | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sign |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Languages of Poland | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Official language | |||||||

| Minority languages |

| ||||||

| Related | |||||||

| Turkic languages | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proto-language |  | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common Turkic |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oghur | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Disputed classification | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Potentially Turkic languages | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Creoles and pidgins | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||