| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Zaduszki" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (September 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Zaduszki (Polish: [zaˈduʂki] ) or Dzień Zaduszny (Polish: [ˈd͡ʑɛɲ zaˈduʂnɘ] ) is a Polish name for the Commemoration of All the Faithful Departed (All Souls' Day) on 2 November. The word Zaduszki originating from Dzień Zaduszny, can be roughly translated into English as "the day of prayers for the souls". On this day people visit cemeteries to light candles and pray for the souls of their faithful departed, especially those believed to be in purgatory.

The annual celebration in the liturgical year of All Souls' day was standardized and put on 2 November by St. Odilo of Cluny by the end of the 10th century. In 1311, by the decision of the Holy See, All Souls' Day was introduced into the Roman Rite and the General Roman Calendar.

In folk understanding, All Saints' Day was viewed as the eve of the main commemoration of Dzień Zaduszny, when most folk customs and rituals took place.

It was believed that during the days of Zaduszki in the autumn, the spirits of deceased relatives visited their old homes by gathering near the windows or on the left side of the main doorway. Eventually, it was believed that as they entered the house, they would warm themselves by the home's hearth and search for the commemoration meal prepared for them. Prior to returning to the Otherworld, the souls went to church for a special nighttime mass by the dead priest's soul. The living were not allowed to watch the dead; those who broke this rule would be punished severely.

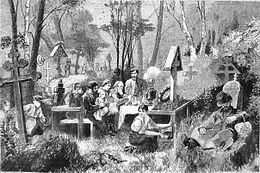

The ritual of Zaduszki began with caring for the cemeteries: people tidied the graves of their relatives, decorated them with flowers, lit the candles; a collective prayer for the dead was organized, and concluded with having the priest bless the graves with prayers and holy water. Homeowners in Eastern Poland prepared to meet the dead by cleaning and preparing the house for the visit; covering the floor with sand, leaving the door or window open, moving a bench closer to the hearth. And on this bench, a dish of water, a comb, and a towel were placed, so that the souls could wash themselves and comb their hair.

Women would traditionally bake special bread for souls on the Zaduszki holiday. The bread was brought to the cemetery and given to the poor, children, clerics, or simply left on the graves in a similar vein to modern-day 'trick-or-treating'. Families have traditionally tried to give out as much as possible (in some places, they baked and gave out up to 200–300 buns of bread), believing that this would help to bring in wealth and prosperity.

During Zaduszki days, people followed many taboos: by not working in the field, not doing any important household work, and by not starting a trip. According to Polish beliefs, on Zaduszki Eve, one had to go to bed as early as possible, in order not to distract the dead from celebration of their holiday. The remains of the commemorative dinner were not allowed to be removed from the table until morning; going outside and taking out trash or water were tabooed, as well. All the dogs should remain on their chains that night. If someone needed to take out the trash or pour the water out next to the house, he/she would say a special warning by-word: "Move over, soul, or I'll spill my trash/water on you!" Whitening of the oven or walls of the house was also prohibited, in order not to spray the dead with clay and lime.

In other Slavic countries

Similar observances exist not just in Poland, but in other Slavonic countries as well, such as Serbia, Slovenia, North Macedonia, Bulgaria, Croatia and Slovakia. These are known by a variety of names:

- Belarusian: Дзяды, lit. 'Grandfathers'

- Bulgarian: Задушница, Душница, Мъртви съботи, Мъртъв ден, Ден на мъртвите

- Croatian: Dušni dan, Mrtvih dan, lit. 'Soul Day, Day of the Dead'

- Macedonian: Задушница, Мртва сабота

- Russian: Родительская суббота, Урочные дни, lit. 'Parental Saturday, Fixed Day'

- Serbian: Задушнице / Zadušnice

- Slovak: Spomienkový deň, Pamiatka zosnulých, Dušičky

However, unlike Roman Catholic Poland, in Orthodox Slavonic countries there are four of these events in a calendar year: the one on the first Saturday in November, like All Hallow's Eve / All Saints in Roman Catholic, Anglican, and some Lutheran communities, called The St Demetrius Day Zadušnice/Zadušnica, but also the one before the start of the Great Lent (as a rule in March), the one before the Pentecost, and the one before Michaelmas.

References

- Williams, Victoria (21 November 2016). Celebrating Life Customs around the World: From Baby Showers to Funerals, Volume 1-3. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 979-8-216-05857-1.

See also

| Polish folk customs and traditions | |

|---|---|

| Winter | Konik • Koza • Turoń • Podłaźniczka • Gromnica • Jemioła • Ścięcie śmierci • Podkoziołek • Popielcowe klocki • Wkupne do bab • Zapusty • Ostatki • Przebierańce • Comber • Herody • Kolęda |

| Spring | Marzanna • Zielone Świątki • Gregorianki • Hanging of Judas • Pucheroki • Święconka • Śmigus-dyngus • Emaus fair • Turki • Dziady śmigustne • Śmiergust • Siuda Baba • Kurek dyngusowy • Pisanki • Walatka • Easter palm • Jezusek Palmowy • Funeral of żur and a herring • Roduś • Rękawka • Żandary • Siwki • Maypole • Fat Thursday • Gorzkie żale |

| Summer | Noc Kupały • Sobótka • Wyzwolenie kosiarza • Oborywanie przepiórki • Ścinanie kani • Zażynki |

| Autumn | Dożynki • Dziady • Zaduszki • Katarzynki • Andrzejki |

| Attire • Traditional music • Folk dances • Folk beliefs | |