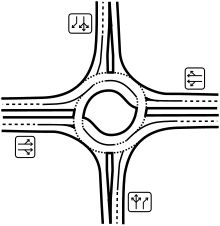

Movement within a roundabout in right-hand traffic; note the anticlockwise circulation

Movement within a roundabout in right-hand traffic; note the anticlockwise circulation Movement within a roundabout in left-hand traffic; note the clockwise circulation

Movement within a roundabout in left-hand traffic; note the clockwise circulation

A roundabout, a rotary and a traffic circle are types of circular intersection or junction in which road traffic is permitted to flow in one direction around a central island, and priority is typically given to traffic already in the junction.

In the USA, engineers use the term modern roundabout to refer to junctions installed after 1960 that incorporate various design rules to increase safety. Compared to stop signs, traffic signals, and earlier forms of roundabouts, modern roundabouts reduce the likelihood and severity of collisions greatly by reducing traffic speeds and minimizing T-bone and head-on collisions. Variations on the basic concept include integration with tram or train lines, two-way flow, higher speeds and many others.

For pedestrians, traffic exiting the roundabout comes from one direction, instead of three, simplifying the pedestrian's visual environment. Traffic moves slowly enough to allow visual engagement with pedestrians, encouraging deference towards them. Other benefits include reduced driver confusion associated with perpendicular junctions and reduced queuing associated with traffic lights. They allow U-turns within the normal flow of traffic, which often are not possible at other forms of junction. Moreover, since vehicles that run on gasoline typically spend less time idling at roundabouts than at signalled intersections, using a roundabout potentially leads to less pollution. When entering vehicles only need to give way, they do not always perform a full stop; as a result, by keeping a part of their momentum, the engine will require less work to regain the initial speed, resulting in lower emissions. Research has also shown that slow-moving traffic in roundabouts makes less noise than traffic that must stop and start, speed up and brake.

Modern roundabouts were first standardised in the UK in 1966 and were found to be a significant improvement over previous traffic circles and rotaries. Since then, modern roundabouts have become commonplace throughout the world, including Australia, the United Kingdom and France.

History

Origins and demise of traffic circles

Circular junctions existed before roundabouts, including:

- 1768 United Kingdom: The Circus in the city of Bath, Somerset was completed. This was constructed based on architectural considerations and not for traffic purposes.

- 1780 (ca.) France: The Place de l'Étoile around the Arc de Triomphe in Paris.

- 1791 US: Pierre Charles L'Enfant (who came to America in 1776) designed a plan of Washington, D.C., which was then being planned. This design contained several large places/street crossings. Many of them had a rectangular outer outline, but within each was a place, around which the streets should be built, thus reducing the number of arms/legs of each crossing.

- 1821 US: The Governor's Circle (later renamed Monument Circle) of Indianapolis, Indiana (which gave the city the nickname "The Circle City");

- 1877 France: The French architect Eugène Hénard was designing one-way circular intersections.

- 1879 Netherlands: The Keizer Karelplein in Nijmegen.

- 1899 Germany: Brautwiesenplatz (Bride Meadow('s) Place) in Görlitz.

- 1904 US: Columbus Circle in Manhattan, New York.

- 1905 US: American architect William Phelps Eno favored small traffic circles.

He re-designed New York City's famous Columbus Circle, which was finished in 1905. - 1907 US: Architect John McLaren designed one of the first American traffic circles for both autos and streetcars (trams) in the Hanchett Residence Park in what is now San Jose, California.

- 1909 United Kingdom: The first British circular junction was built in Letchworth Garden City.

Although some may still be referred to as roundabouts, the operating and entry characteristics of these traffic circles differed considerably from modern roundabouts.

Circular intersections were built in the United States, though many were large-diameter 'rotaries' that enabled high-speed merge and weave manoeuvres. Older-style traffic circles may control entering traffic by stop signs or traffic lights. Many allow entry at higher speeds without deflection, or require a stop and a 90-degree turn to enter. Because these circumstances caused a lot of vehicle collisions, construction of traffic circles and rotaries ceased in the 1950s, and some were removed.

-

National Register of Historic Places plaque on the first traffic circle in the United States, at the intersection of River and Pleasant streets in Yarmouth, Massachusetts

-

Thomas Circle in Washington, D.C., 1922

Thomas Circle in Washington, D.C., 1922

-

Traffic ten abreast traverses the Place de l'Étoile. This traffic circle surrounds the Arc de Triomphe at the intersection of ten two-way and two one-way streets. It has no lane markings.

Traffic ten abreast traverses the Place de l'Étoile. This traffic circle surrounds the Arc de Triomphe at the intersection of ten two-way and two one-way streets. It has no lane markings.

1960s development of modern roundabouts

Widespread use of the modern roundabout began when the UK's Transport Research Laboratory engineers re-engineered and standardised circular intersections during the 1960s. Frank Blackmore led the development of the "priority rule" and subsequently invented the mini-roundabout to overcome capacity and safety limitations. The priority rule was found to improve traffic flow by up to 10%. In 1966, the United Kingdom adopted a rule at all circular junctions that required entering traffic to give way to circulating traffic. A Transportation Research Board guide reports that the modern roundabout represents a significant improvement, in terms of both operations and safety, when compared with older rotaries and traffic circles. The design became mandatory in the United Kingdom for all new roundabouts in November 1966. Australia and other British-influenced countries were the first outside the UK to build modern roundabouts.

Spread in Europe and North America since 1970s

- In 1951, Cyprus, British Crown colony back then, adopted the roundabout in the main cities.

- In the 1970s, France and Norway adopted the modern roundabout.

- In 1973, the U.S. city of Seattle began installing small traffic circles within existing intersections to calm traffic. As of 2021, the city has installed over 1,200 traffic circles, primarily in residential neighborhoods.

- In 1980, Switzerland had 19 roundabouts.

- In 1980, Norway had 15 roundabouts.

- In the early 1980s, single-lane roundabouts (or mini-roundabouts) were also introduced in the Netherlands. It began in the relatively sparsely populated northern and eastern Netherlands because of fears that the roundabouts would not be able to cope with the traffic density of the Randstad; however, when it appeared the single-lane roundabouts had an even higher capacity than signalised intersections, they were constructed en masse in the western Netherlands as well.

- In 1983, France adopted the yield-at-entry rule on national routes; since then the country's roundabouts have proliferated.

- In 1985, Norway put up yield signs at the entries to all its roundabouts. After this, safety and traffic flow rapidly improved, and Norwegian roundabouts increased from 15 in 1980, to 350 in 1990, to 500 in 1992.

- In 1987, Switzerland introduced the yield-at-entry rule; since then its roundabouts increased from 19 in 1980 to 220 in early 1992, while 500 more were being considered.

- In the late 1980s, the Netherlands saw significant growth with about 400 roundabouts constructed in just 6 years. Construction accelerated in the 1990s, and by 2001, there were an estimated 1,500 to 1,800 roundabouts in the Netherlands, more than half of which were located within built-up areas.

- In 1990, the US constructed its first modern roundabout, although older roundabouts have been somewhat common in parts of the Northeast (called rotaries or traffic circles).

- In 1991, France was building 1,000 roundabouts every year.

- As modern roundabouts rose in popularity in the 1980s, the old traffic circles fell out of favour and many were converted into modern roundabouts or other types of intersections.

- In 1999, Canada built its first modern roundabout.

- As of the beginning of the 21st century, roundabouts were in widespread use in Europe. For instance:

- In 2010, France had more than 30,000 roundabouts.

- There were around 25,000 in the United Kingdom in 2015.

-

Roundabout, Haarlem, Netherlands, 1990. Cyclists may also be users of a roundabout.

-

Small roundabout in Barzio, Italy

-

Roundabout in Straßwalchen, Austria

Roundabout in Straßwalchen, Austria

-

Roundabout in the centre of Colombo, Sri Lanka

-

Double-lane Raindrop Fountain Roundabout in Zenica, Bosnia and Herzegovina, where roundabouts replaced all traffic lights since 2011.

Double-lane Raindrop Fountain Roundabout in Zenica, Bosnia and Herzegovina, where roundabouts replaced all traffic lights since 2011.

-

Roundabout signs in Linköping, Sweden

-

A roundabout sign example used in the UK

A roundabout sign example used in the UK

North American introduction since 1990s

Modern roundabout in Hughesville, Maryland in 2020

Modern roundabout in Hughesville, Maryland in 2020 Modern roundabout intersection in Murrayville, Langley, British Columbia

Modern roundabout intersection in Murrayville, Langley, British Columbia Roundabout sign in Ontario, Canada

Roundabout sign in Ontario, Canada

In the United States modern roundabouts emerged in the 1990s after years of planning and educational campaigning by Frank Blackmore and Leif Ourston, who sought to bring the by then well-established increased safety and traffic flow in other countries to America. The first was constructed in Summerlin, Nevada, in 1990 and was followed by another the following year. This roundabout occasioned dismay from residents, and a local news program said about it, "Even police agree, can be confusing at times." Between 1990 and 1995, numerous modern roundabouts were built in California, Colorado, Florida, Maryland, Nevada, and Vermont.

Municipalities introducing new roundabouts often were met with some degree of public resistance, just as in the United Kingdom in the 1960s.

- American confusion at how to enter and especially how to exit a roundabout was the subject of mockery such as featured in the film European Vacation (1985).

- A 1998 survey of municipalities found public opinion 68% opposed prior to construction, changing thereafter to 73% in favour.

- A 2007 survey found public support ranging from 22% to 44% prior to construction, and several years after construction was 57% to 87%.

- By 2011, however, some 3,000 roundabouts had been established, with that number growing steadily.

In the mid-2010s, about 3% of the then circa 4,000 U.S. modern roundabouts were located in Carmel, Indiana, whose mayor James Brainard had been actively promoting their construction; because of increased safety, injuries caused by car accidents in the city dropped by 80% after 1996. As of December 2015 there were about 4,800 modern roundabouts in the United States. As an example, Washington state contained about 120 roundabouts as of October 2016, all having been built since 1997, with more planned.

The first Canadian traffic circles were in Edmonton. There were 7 such by 1954. However, they didn't gain popularity in the rest of the country until the 1990s. They became increasingly popular amongst traffic planners and civil engineers in the 15 years thereafter due to their success in Europe. By 2014 there were about 400 roundabouts in Canada at the time (most in Quebec, Alberta, British Columbia and Ontario), or one per 90,000 inhabitants (compared to one per 84,000 inhabitants in the United States that year).

Modern roundabout

Roundabout sign examples Vienna Convention mandatory

Vienna Convention mandatory Vienna Convention warning

Vienna Convention warning MUTCD warning

MUTCD warning Give Way

Give Way(Yield)Right-hand traffic shown. Direction arrows are mirrored for left-hand traffic

A "modern roundabout" is a type of looping junction in which road traffic travels in one direction around a central island and priority is given to the circulating flow. Signs usually direct traffic entering the circle to slow and to give way to traffic already on it.

Because low speeds are required for traffic entering roundabouts, they are physically designed to slow traffic entering the junction to improve safety, so that the roads typically approach the junction radially; whereas older-style traffic circles may be designed to try to increase speeds, and have roads that enter the circle tangentially.

Roundabouts are normally not used on controlled-access highways because of the low speed requirement, but may be used on lower grades of highway such as limited-access roads. When such roads are redesigned to incorporate roundabouts, traffic speeds must be reduced via tricks such as curving the approaches.

Many traffic circles have been converted to modern roundabouts, including the former Kingston traffic circle in New York and several in New Jersey. Others have been converted to signalised intersections, such as the Drum Hill Rotary in Chelmsford, Massachusetts, which is now six lanes wide and controlled by four separate intersections.

Japan was first introduced to roundabouts in September 2014 to stop major accidents and traffic jams.

Terminology

The word roundabout dates from early 20th-century use in the United Kingdom. A roundabout is also a traditional English name given to amusement rides known as a carousel, or a merry-go-round in other English-speaking countries.

In U.S. dictionaries the terms roundabout, traffic circle, road circle and rotary are synonyms. However, several experts such as Leif Ourston have stressed the need to distinguish between the characteristics of the modern roundabout and the nonconforming traffic circle:

- Modern roundabout

- Entering traffic yields to circulating traffic

- Entering traffic aims at the centre of the central island and is deflected slowly around it

- Upstream roadway often flares at entry, adding lanes

- Nonconforming traffic circle

- Entering traffic cuts off circulating traffic

- Entering traffic aims to one side of the central island (right side for right-hand traffic) and proceeds straight ahead at speed

- Lanes are not added at entry

The U.S. Department of Transportation adopted the term modern roundabout to distinguish those that require entering drivers to give way to others. Many old traffic circles remain in the northeastern US. Some modern roundabouts are elongated to encompass additional streets, but traffic always flows in a loop.

Rotary

In the United States, traffic engineers typically use the term rotary for large-scale circular junctions between expressways or controlled-access highways. Rotaries of this type typically feature high speeds inside the circle and on the approaches.

In the United States' New England region, however, a "rotary" is typically used as the general term for all roundabouts, including those with modern designs. State laws in these states mandate that traffic already driving in the rotary always has the right of way. For instance, in Massachusetts, "Any operator of a vehicle entering a rotary intersection shall yield the right-of-way to any vehicle already in the intersection." In Rhode Island entering vehicles "Yield to vehicles in the roundabout."

Other terms

In the dialect used in the Scottish city of Dundee, circle is used to refer to roundabouts.

In the English West Midlands, island is in common use.

In the Channel Islands a third type of roundabout, known as "Filter in Turn", exists. Here approaching drivers neither give way to traffic on the roundabout, as normal, nor have priority over it, but take it in turns to enter from each. Almost all of Jersey's roundabouts are of this type.

Operation and design

| This section includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. Please help to improve this section by introducing more precise citations. (December 2013) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The fundamental principle of modern roundabouts is that entering drivers give way to traffic within the roundabout without the need for traffic signals. Conversely, older traffic circles typically require circling drivers to give way to entering traffic. Roundabouts may also have an interior lane. Generally, exiting directly from an inner lane of a multi-lane roundabout is permitted, given that the intersecting road has as many lanes as the roundabout. By contrast, exiting from an inner lane of an older traffic circle is usually not permitted and traffic must first move into the outside lane.

Vehicles circulate around the central island in one direction at speeds of 25–40 km/h (15–25 mph). In left-hand traffic countries they circulate clockwise (looking from above); in right-hand traffic, anticlockwise.

Multi-lane roundabouts are typically less than 75 metres (250 ft) in diameter; older traffic circles and roundabout interchanges may be considerably larger. Roundabouts are roughly the same size as signalled intersections of the same capacity.

Design criteria include:

- Right-of-way: Whether entering or circling vehicles have the right of way. The New Jersey Driver's Manual recommends that, in the absence of flow control signs, traffic yields based on "the circle's historically established traffic flow pattern", and there are no set rules. In New England, Washington, D.C., and New York State, entering traffic yields, as is the norm in virtually all countries outside of the U.S.

- Angle of entry: Angles range from glancing (tangential) that allow full-speed entry to 90 degree angles (perpendicular). Deflection is required to avoid vehicles entering at excessive speeds.

- Traffic speed: High entry speeds (over 30 mph or 48 km/h) require circulating vehicles to yield, often stopping, which lowers capacity and increases crash rates compared to modern roundabouts.

- Lane changes: Allowed or not

- Diameter: The greater the traffic, the larger the circle.

- Island function: Parking, parks, fountains, etc.

Islands

Modern roundabouts feature a central island and sometimes pedestrian islands at each entry or exit often for decoration.

Denmark has begun widespread adoption of particular high islands, or if not possible, obstacles such as hedges or a ring of trees in larger examples. This is done to further increase the safety benefits of roundabouts, as the obstacles have been found to discomfort drivers more so than the roundabout itself compared to conventional intersections, thus initiating further observation and care taking of the driver. In Denmark, it was found to decrease accidents in roundabouts by 27% to 84% depending on height and type. In studies, heights of 0-0.9, 1-1.9 and 2+ metres were evaluated. It was found that for all heights, especially accidents leading to human injuries were reduced the most, by -47% to -84% for the aforementioned heights. The level of irritation to drivers is not to be understated, as it is the crucial point of the design: to force drivers to pay attention to the sides of the driving direction. This leads to drivers complaining about these designs, as Denmark in most regards embraces designing road infrastructure, such that the wanted driving behaviour leads to comfort i.e., lane width corresponding to speed limit and obstacles encouraging slowdown near points of safety concern such as schools. Such is the controversy for drivers that seasoned driving teachers complain about this discomfort a decade after its safety is proven and adoption widespread.

Central

The central island may be surrounded by a truck apron that is high enough to discourage drivers from crossing over it, but low enough to allow wide or long vehicles to navigate the roundabout. The island may provide a visual barrier, to alert approaching drivers to the presence of the roundabout, and to encourage drivers to focus on the traffic in the path of the circle. A visual barrier significantly reduces the accident rate. Otherwise, vehicles anywhere in or near the circle can cause those entering to stop and wait for them to pass, even if they are opposite, which unnecessarily reduces traffic flow. The barrier may be a landscaped mound, a raised wall, a tree or tall shrubs. Road signage or flagpoles may be erected at the top of a landscaped mound.

Some communities use the island for monuments, the display of large public art or for a fountain. Pedestrians may be prohibited from crossing the circling lane(s). Access to the central island requires an underpass or overpass for safety.

Art installations

Roundabouts have attracted art installations around the world:

- Bend, Oregon (United States); Bend's Roundabout sculptures were honoured by Americans for the Arts as among the 37 most innovative approaches to Public Art in the country.

- Fuerteventura, Canary Islands (Spain); Local government displayed sculptures at several roundabouts.

- Many countries in Europe (France first, but also Germany, Austria, Italy, Spain, and others) show the widespread use of roundabouts as art installations.

- An inventory of roundabouts in France, made by Marc Lescuyer, listed 3,328 roundabouts with artistic decor early in 2010.

- The Minerva Roundabout in Guadalajara, Mexico, is one of the city's most famous monuments. It features the goddess Minerva standing on a pedestal, surrounded by a large fountain, with an inscription saying "Justice, wisdom and strength guard this loyal city".

- Several famous monuments in Europe, such as the Gate of Alcalá in Madrid, Spain or the Arc du Triomphe in Paris, France, have been isolated from street traffic by means of a roundabout.

- The Garces Memorial Circle in Bakersfield, California contains a statue to Father Francisco Garces.

- In the Philippines, the town of Ipil, Zamboanga Sibugay has an Obelisk containing art and the Baybayin script.

Pedestrian

For larger roundabouts, pedestrian islands at each entry/exit encourage drivers to slow and prepare to enter the circle. They also provide a refuge where pedestrians may pause mid-crossing. Vehicles or bicycles entering or exiting the roundabout must yield to all traffic including pedestrians.

Pedestrian crossing

Pedestrian crossings at each entry/exit may be located at least one full car length outside the circle. The extra space allows pedestrians to cross behind vehicles waiting to enter the circle, and to allow exiting vehicles to stop for pedestrians without obstruction. Each pedestrian crossing may traverse a pedestrian island for protection that also forces drivers to slow and begin to change direction, encouraging slower, safer speeds. On the island, the pedestrian crossing may become diagonal, to direct the gaze of those crossing into exiting traffic.

Bicycles

Physically separated bikeways best protect cyclists. Less optimally, terminating cycle lanes well before roundabout entrances requires cyclists to merge into the stream of motor traffic, but keeps cyclists in full view of drivers, at some cost in motor vehicle speed. Cyclists may also be permitted to use pedestrian crossings.

Traditional cycle lanes increase vehicle–bicycle collisions. When exiting, a motorist must look ahead to avoid colliding with another vehicle or with pedestrians on a pedestrian crossing. As the intersection curves away from the exit, the path of an exiting vehicle is relatively straight, and so the motorist may often not slow substantially. To give way to a cyclist on the outside requires the exiting motorist to look toward the rear, to the perimeter. Other vehicles can obstruct the driver's view in this direction, complicating the motorist's task. The more frequent requirements for motorists to slow or stop reduce traffic flow. A 1992 study found that the risk to cyclists is high in all such intersections, but much higher when the junction has a marked bicycle lane or sidepath around its perimeter. Cycle lanes were installed at Museum Road, Portsmouth, but were replaced by a narrowed carriageway to encourage lane sharing.

The roundabout at the Brown Road and Loop 202 interchange in Mesa, Arizona, adopts a U.S.-recommended design. On-street pavement markings direct cyclists to enter the sidewalk at the end of the bike lane. Cyclists who choose to travel on the wide sidewalk, cross roundabout arms perpendicularly, well outside the circle. A pedestrian island allows pedestrians and cyclists to cross one lane at a time.

Protected roundabouts (or Dutch roundabout) were developed in the Netherlands, with cyclists separated from vehicles using dedicated lanes. As cyclists will conflict with motorists at the exit arms of the motorised roundabout, priority must be established. In the Netherlands, cyclists will normally be given priority to promote cycling over driving. As well as their use in the Netherlands and Denmark, these designs have been subsequently built in the United Kingdom and Ireland.

-

The Hovenring bicycle roundabout in the Netherlands is an innovative design, completely separating bicycles from vehicular traffic.

The Hovenring bicycle roundabout in the Netherlands is an innovative design, completely separating bicycles from vehicular traffic.

-

Pavement markings invite cyclists to enter sidewalk on approach to roundabout in Mesa, Arizona. Cyclists are still permitted to use the roundabout like any other vehicle.

Pavement markings invite cyclists to enter sidewalk on approach to roundabout in Mesa, Arizona. Cyclists are still permitted to use the roundabout like any other vehicle.

-

Cyclists can choose to ride on the sidewalk on far right, or in the main lanes of this roundabout in Mesa, Arizona.

Cyclists can choose to ride on the sidewalk on far right, or in the main lanes of this roundabout in Mesa, Arizona.

-

3D view of a protected roundabout, as commonly used in the Netherlands

3D view of a protected roundabout, as commonly used in the Netherlands

Capacity and delays

The capacity of a roundabout varies based on entry angle, lane width, and the number of entry and circulating lanes. As with other types of junctions, operational performance depends heavily on the flow volumes from various approaches. A single-lane roundabout can handle approximately 20,000–26,000 vehicles per day, while a two-lane design supports 40,000 to 50,000.

Under many traffic conditions, a roundabout operates with less delay than signalised or all-way stop approaches. Roundabouts do not stop all entering vehicles, reducing both individual and queuing delays. Throughput further improves because drivers proceed when traffic is clear without waiting for a signal to change.

Roundabouts can increase delays in locations where traffic would otherwise often not be required to stop. For example, at the junction of a high-volume and a low-volume road, traffic on the busier road would stop only when cross traffic was present, otherwise not having to slow for the roundabout. When the volumes on the roadways are relatively equal, a roundabout can reduce delays, because half of the time a full stop would be required. Dedicated left turn signals (in countries where traffic drives on the right) further reduce throughput.

Roundabouts can reduce delays for pedestrians compared to traffic signals, because pedestrians are able to cross during any safe gap rather than waiting for a signal. During peak flows when large gaps are infrequent, the slower speed of traffic entering and exiting can still allow crossing, despite the smaller gaps.

Studies of roundabouts that replaced stop signs and/or traffic signals found that vehicle delays were reduced 13–89 percent and the proportion of vehicles that stopped was reduced 14–56 percent. Delays on major approaches increased as vehicles slowed to enter the roundabouts.

Roundabouts have been found to reduce carbon monoxide emissions by 15–45 percent, nitrous oxide emissions by 21–44 percent, carbon dioxide emissions by 23–37 percent and hydrocarbon emissions by 0–42 percent. Fuel consumption was reduced by an estimated 23–34 percent.

Capacity modelling

Many countries have researched roundabout capacity. The software can help calculate capacity, delay and queues. Packages include ARCADY, Rodel, Highway Capacity Software and Sidra Intersection. ARCADY and Rodel are based on the Transport Research Laboratory mathematical model. The TRL approach is derived from empirical models based on geometric parameters and observed driver behaviour with regard to lane choice. Sidra Intersection software includes roundabout capacity models developed in Australia and the US.

Research on Australian roundabouts was conducted in the 1980s at the Australian Road Research Board (ARRB). Its analytical capacity and performance models differ from the TRL model significantly, following a lane-based gap-acceptance theory including geometric parameters.

Research on U.S. roundabouts sponsored by the Transportation Research Board (TRB) and Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) culminated in a capacity model that was included in the Highway Capacity Manual (HCM) Edition 6 and the TRB-FHWA Roundabout Informational Guide (NCHRP Report 672). The HCM Edition 6 model is based on lane-based gap-acceptance theory. A recent NCHRP survey of US state transport agencies found that Sidra Intersection is the most widely used software tool in the US for roundabout analysis.

Safety

Statistically, modern roundabouts are safer for drivers and pedestrians than both older-style traffic circles and traditional intersections. Compared with these other forms of intersections, modern roundabouts experience 39% fewer vehicle collisions, 76% fewer injuries and 90% fewer serious injuries and fatalities (according to a study of a sampling of roundabouts in the United States, when compared with the junctions they replaced). At junctions with stop signs or traffic lights, the most serious accidents are right-angle, left-turn or head-on collisions where vehicles move fast and collide at high impact angles, e.g. head-on. Roundabouts virtually eliminate those types of crashes. Instead, most crashes are glancing blows at low angles of impact. Further, a study based on satellite imagery of all intersections in Australia observed consistently low speeds on roundabouts compared to other intersection types, contributing to reduced injury severity in case of a crash.

Some larger roundabouts take foot and bicycle traffic through underpasses or alternate routes. However, an analysis of the New Zealand national crash database for the period 1996–2000 shows that 26% of cyclists reported injury crashes happened at roundabouts, compared to 6% at traffic signals and 13% at priority controlled junctions. The New Zealand researchers propose that low vehicle speeds, circulatory lane markings and mountable centre aprons for trucks can reduce the problem. The most common roundabout crash type for cyclists, according to the New Zealand study, involves a motor vehicle entering the roundabout and colliding with a cyclist who already is travelling around the roundabout (more than half of cyclist/roundabout crashes in New Zealand fall into this category). The next most common crash type involves motorists leaving the roundabout colliding with cyclists who are continuing farther around the perimeter.

Vision-impaired pedestrians

Poorly designed walkways increase risks for the vision-impaired, because it is more difficult than at a signalised intersection to audibly detect whether there is a sufficient gap in traffic to cross safely. At a signalised intersection, traffic comes to a stop, and an audible sound can be generated to indicate that it is time to cross.

This issue has led to a conflict in the United States between the vision-impaired and civil engineering communities. One solution is to provide manually-operated pedestrian crossing signals at each entry. This increases construction and operation costs, and requires some way to disrupt traffic long enough for the pedestrian to cross (such as a HAWK beacon) that defeats the purpose of the roundabout. Signalisation also increases delays for most pedestrians during periods of light traffic, since pedestrians need to wait for a signal to change before (legally) crossing.

Signalised pedestrian crossings are normally used on large-diameter roundabout interchanges rather than small-diameter modern roundabouts.

Types of circular intersections

| This article needs editing to comply with Misplaced Pages's Manual of Style. Please help improve the content. (October 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Large roundabouts, such as those used at motorway junctions, typically have two to six lanes and may include traffic lights to regulate flow.

Some roundabouts have a divider or subsidiary deflection island, by means of which is provided a "free flow" segregated left- (or right-) turn lane (for the UK see Design Manual for Roads and Bridges TD 51/03) between traffic moving between two adjacent roads, and traffic within the roundabout, enabling drivers to bypass the roundabout.

Gyratory system

The term "gyratory" (for example, Hanger Lane gyratory) is sometimes used in the United Kingdom for a large circular intersection with non-standard lane markings or priority arrangements, or where there are significant lengths of carriageway between the entry arms, or when buildings occupy the central island.

In the 21st century several gyratory systems in London have been removed, including Tottenham Hale and Elephant and Castle.

Smaller, small and mini-roundabouts

As the overall or external size of a roundabout (in the UK referred to as the Inscribed Circle Diameter – ICD) is reduced, so the maximum practicable (and prescribed) diameter for the central island is also reduced, whilst the width of the circulatory carriageway increases (due to the greater width of vehicle swept path at smaller turning radii). In most cases, this results in it being too easy – certainly when traffic is light relative to capacity – for drivers to traverse the roundabout at relatively high speed, with scant regard for road markings or the potential dangers to self or conflicts with other road users. To mitigate this risk, a proportion of the circulatory carriageway – an annulus around the central island – is segregated from general use by demarcation lines and differentiated from the outer annulus of the carriageway by a combination of a slightly raised surface, adverse crossfall, contrasting colours and textures and demarcating lines. The effect of this is to discourage drivers from taking a more direct path through the roundabout, their line of least resistance is more tightly curved (and therefore slower) but more bearable. The inner annulus provides for the trailing axles of longer or articulated vehicles to sweep across the inner annulus, which is therefore known as an over-run area (in UK usage), truck apron, or mountable apron.

The smaller the roundabout, the more such mitigation measures are likely to be abused – the less effective they will be. In the UK the minimum size for roundabouts with raised islands is 28 metre diameter ICD with a 4-metre diameter island. This threshold being driven primarily by vehicle geometry – which is globally relatively consistent – rather than driver behaviour, it is adopted in other jurisdictions too. Below this minimum size, the mini-roundabout prevails.

Mini-roundabouts

After developing the offside priority rule, Frank Blackmore, of the UK's Transport Research Laboratory, turned his attention to the possibility of a roundabout that could be built at sites lacking room for a conventional roundabout.

-

Small roundabout in Kargilik, Xinjiang, China

Small roundabout in Kargilik, Xinjiang, China

-

Mini-roundabout in Uftrungen, Germany

-

A mini-roundabout in the UK, where a painted white circle is used as centre. The arrows show the direction of traffic.

A mini-roundabout in the UK, where a painted white circle is used as centre. The arrows show the direction of traffic.

Mini-roundabouts can incorporate a painted circle or a low dome but must be fully traversable by vehicles. Motorists can drive over them when there is no other traffic, but it is dangerous to do so otherwise. Once the practice is established it may be difficult to discourage. Mini-roundabouts use the same right-of-way rules as standard roundabouts but produce different driver behaviour. Mini-roundabouts are sometimes grouped in pairs (a double mini-roundabout) or in "chains", simplifying navigation of otherwise awkward junctions. In some countries road signs distinguish mini-roundabouts from larger ones.

Mini-roundabouts are common in the UK, Ireland and Hong Kong (particularly on Hong Kong Island), as well as Irapuato in Mexico.

In the UK and also in other jurisdictions that have adopted mini-roundabouts, to drive across the central disc or dome when it is practicable to avoid it is an offence. Vehicles are required to treat the painted circle as if it were a solid island and drive around it. Some local authorities paint double white lines around the circle to indicate this, but these require permission from the Secretary of State for Transport. The central dome also must be able to be overrun by larger vehicles.

In the UK – and also in other highway jurisdictions – the maximum size for a mini roundabout is 28 metre (30 yard) ICD (inscribed circle diameter).

Raindrop roundabouts

These roundabouts do not form a complete circle and have a "raindrop" or "teardrop" shape. They have also been used at bowtie intersections, replacing traffic signals that are inefficient without a turning lane. In addition to their use at intersections, raindrop roundabouts are also used in dogbone interchanges (described below).

Balcony roundabout

A balcony roundabout is just an elevated roundabout. They are constructed in such a way that vulnerable road users can cross underneath the roundabout. Footpaths and cycle paths along the different roads connect to the square under the roundabout. Vulnerable road users do not interfere with motorised traffic on the roundabout, reducing the risk of collision.

Turbo roundabouts

In the Netherlands, Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, the United Kingdom, Finland, Spain, Poland, Hungary, Slovenia, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, North Macedonia, Croatia, Germany, and the U.S. states of California and Florida, a relatively new type of two-lane roundabout designs is emerging, called "turbo roundabouts". These designs require motorists to choose their direction before entering the roundabout, thereby eliminating many conflicting paths and choices on the roundabout itself so that traffic safety is increased, as well as speed and capacity. These designs, seen from above, typically result in a spiralling flow of traffic. One minor drawback is that turbo roundabouts are often marked out such that a U-turn by means of the roundabout is not possible for drivers approaching on certain arms.

Several variations of turbo roundabouts exist. They are frequently designed for the intersection of a major road crossing a road with less traffic.

An early application of the principle was a six-arm and therefore relatively large (and fast) non-circular roundabout at Stairfoot, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, which was given spiral marking about 1984. At that time the method was considered experimental and needed special consent from central authorities. The turbo roundabout was formally developed in 1996 in the Netherlands by Lambertus Fortuijn, a researcher from the Delft University of Technology. Similar roundabouts, with spiralling lane markings, have been used for many years in the UK e.g. the A176/A127 (eastbound) at Basildon, Essex (51°33′41″N 0°27′11″E / 51.561399°N 0.452934°E / 51.561399; 0.452934). However, it was not until 1997 that the UK's national highway authorities published guidance (DMRB TA-78/97) that in effect endorsed the use of spiral markings in certain circumstances.

Turbo roundabouts can be built with raised lane separators (common in the Netherlands) or with lane markings only. The use of raised lane separators prevents road users from weaving (thereby reducing conflicts) but can make manoeuvring more difficult for large vehicles.

According to simulations, a two-lane roundabout with three exits should offer 12–20% greater traffic flow than a conventional, three-lane roundabout of the same size. The reason is reduced weaving that makes entering and exiting more predictable. Because there are only ten points of conflict (compared with 8 for a conventional single lane roundabout, or between 32 and 64 with traffic signal control), this design is often safer as well. Research and experiments show that traffic accidents are reduced by 72% on turbo roundabouts compared to multi-lane roundabouts, which have 12 points of conflict. Research at Windesheim University also shows that turbo roundabouts reduce accidents including casualties by some 75% when compared to regular intersections, and by 61% compared to single-lane roundabouts. The same research made it very clear that it is safer for cyclists not to have priority over motor vehicles on the roundabout, than to have it. At least 70 have been built in the Netherlands, while many turbos (or similar, lane splitting designs) can be found in southeast Asia. Multi-lane roundabouts in the United States of America are typically required to be striped with spiral markings, as most states follow the federal Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices.

Sub-sea roundabouts

A new development is the roundabout below the seabed, in locations where multiple undersea traffic tunnels join. The first such roundabout is in the Eysturoy Tunnel (Eysturoyartunnilin), opened in December 2020 in the Faroe Islands. It connects the main island Streymoy with two locations on the island Eysturoy that are separated by a long fjord, Skálafjørður. So, three roads meet at this roundabout. Total length of the system is 11.24 km (6.98 mi). It was the largest ever infrastructure project in the Faroe Islands, estimated to have cost around a billion Danish kroner.

Motorways

See also: Roundabout interchange

Roundabouts are generally not appropriate for placement on motorway or freeway mainlines because the purpose of such facilities is to provide for uninterrupted traffic flow. However, roundabouts are often used for the junction between the slip roads (called ramps in North America) and the intersecting road. A single roundabout, grade separated from the mainlines, may be used to create a roundabout interchange. This type of junction is common in the UK and Ireland.

Alternatively, separate roundabouts also may be used at the slip road intersections of a diamond interchange to create what often is referred to as a "dumbbell interchange", which is increasingly common in both Europe and North America due to its reduced need for wide or multiple bridges. A variation of the dumbbell interchange, often called a "dogbone interchange", occurs when the roundabouts do not form a complete circle but are instead raindrop roundabouts (described above). This configuration reduces conflicts between vehicles entering the raindrop roundabouts from the ramps, reducing queueing and delays, compared with the dumbbell interchange.

Additional use of roundabouts for high-speed junctions is the 3-level stacked roundabout—this is a roundabout interchange where both of the roadway mainlines are grade separated. In the United Kingdom, the M25/A3, M8/M73 and A1(M)/M18 interchanges are examples of this type. These junctions, however, have less capacity than a full free-flow interchange. A similar design to this is the three-level diamond interchange.

Most junctions on Dublin's M50 motorway C-road were built using a standard roundabout interchange. The traffic volume of several of these junctions increased to a level higher than the capacity such roundabouts can accommodate, and in turn, have been converted into partially or fully free-flowing interchanges. One example is the Red Cow interchange. In Northern Ireland, the junction between the M1 and M12 (Craigavon connector motorway) is via a standard roundabout with a raised centre, three onslips and three offslips, and two lanes.

In the city of Malmö, Sweden, a roundabout connects two motorways, E22 from Lund, and the Inner ring road.

In the Netherlands, A6 motorway and A7 motorway used to cross near Joure using a roundabout until October 2017, when the junction was turned into a full Y-interchange. The junction between the A200 and the A9 uses a 3-level stacked roundabout. Near Eindhoven (the Leenderheide junction), the junction for the A2 uses a roundabout. An overpass was built for the A67 from Antwerp to Germany.

Near Liège, Belgium, the Cheratte interchange between the A3/E40 and A25/E25 functions partially as a roundabout, with through traffic allowed to continue without entering the junction and traffic changing between motorways required to use the roundabout.

Rotary interchanges operate with traffic circles rather than roundabouts. Rotary interchanges are common in New England, particularly in the state of Massachusetts, but a European example of a rotary interchange may be found in Hinwil, Switzerland.

Signalised roundabouts

A signalised roundabout is one where one or more entry is controlled by traffic signals, rather than by assumed priority. For each signalised entry there will also be a signalised stopline immediately upstream on the circulatory section. The signals prevent blocking on the roundabout, and balance and improve traffic capacity.

Examples include the M50 in Dublin; the Cherry Street roundabout in Kowloon, Hong Kong; Sheriffhall Roundabout in Edinburgh, Scotland; Newton Circus in Singapore; and many of the roundabouts along the Paseo de la Reforma in Mexico City.

An evolution of the signalised roundabout has been proposed recently. It is based in avoiding stops by eliminating conflict points in roundabouts. This proposed new paradigm (SYROPS) forms platoons of vehicles (e.g. 2 x 3 cars) that arrive at the roundabout with speed identical to the average circulation speed in the roundabout and within the time interval (visualised as a rotating priority sector) assigned to his entrance, avoiding all the conflicts of passage and with it the stops and accelerations required in standard and in signalled roundabouts. Signalling signage is with lights for human drivers and optionally wireless for connected and autonomous vehicles.

"Magic" roundabouts/ring junctions

"Magic roundabouts" direct traffic in both directions around the central island. They are officially known as "ring junctions". The first magic roundabout was constructed in 1972 in Swindon, Wiltshire, United Kingdom, designed by Frank Blackmore, inventor of the mini-roundabout. The roundabout joins five roads and consists of a two-way road around the central island, with five mini-roundabouts meeting the incoming roads.

The name derives from the popular children's television series, The Magic Roundabout, and is considered "magic" because traffic flows in both clockwise and anticlockwise directions. This is achieved by surrounding the main island with one smaller roundabout per entry/exit street. This pattern directs traffic in the usual clockwise (in LHT installations) or counter-clockwise (in RHT installations) manner around each mini-roundabout. Exiting the mini-roundabouts, traffic may proceed around the central island either in the usual direction (via the outer loop), or in the inverse direction (the inner loop). The arrangement offers multiple paths between feeder roads. Drivers typically choose the shorter, most fluid route. Although the safety record is good, many drivers find this system intimidating, and some drivers go to great lengths to avoid them.

Similar systems are found in the Moor End roundabout in Hemel Hempstead (Hertfordshire), which has six intersections; in High Wycombe (Buckinghamshire), the Denham Roundabout in Denham (Buckinghamshire), the Greenstead Roundabout in Colchester (Essex), "The Egg" in Tamworth (Staffordshire) and the Hatton Cross Roundabout in London.

Churchbridge Junction in Staffordshire is a magic gyratory. This type of junction is similar to a magic roundabout, except that the constituent roundabouts are connected by longer lengths of roadway.

-

The Swindon Magic Roundabout

The Swindon Magic Roundabout

-

Map with traffic direction and two routes from Fleming Way to Queen's Drive

Map with traffic direction and two routes from Fleming Way to Queen's Drive

Dutch-style roundabouts for bicycles and pedestrians

See also: Protected intersection § Protected roundabouts

Trams

Tram roundabouts, which are found in many countries, combine roundabouts for individual vehicles with tram lines. Large areas are needed for tram roundabouts that include a junction between tram lines. Tramways usually cross the centre of the roundabout. At busy junctions, this requires traffic lights or special signalling granting the trams priority. However, there are also roundabouts where trams and vehicles share the carriageway. Some roundabouts have a tram stop on the island.

- In France, tram roundabouts commonly have radii between 14 and 22 metres, although some have radii outside this range.

- In some cities, the tramway bisects the roundabout. The French Cerema [fr] considers that the mix of priorities makes these confusing and difficult to understand: a traditional modern roundabout gives the priority to the central ring, while tram roundabouts give priority to the central ring but higher priority still to the tramway. This generates many collisions of cars and trams, between 7 and 10 for each tram roundabout in France between 2006 and 2015 (between 0.37 and 1.01 per year).

- In inner Melbourne, particularly in the inner suburban area of South Melbourne, where the tram network is extensive, tram tracks always pass through the central island, with drivers required to give way to vehicles approaching from their right and to trams approaching from right angles. The Haymarket roundabout between Royal Parade and Elizabeth Street contains a tram-stop, pedestrian crossings, three entering tram lines, traffic signals to stop vehicular traffic at each crossing point when a tram is due, service roads and a pedestrian crossing.

- Brussels tram roundabouts employ multiple configurations. At the Barrière de St-Gilles (Dutch: Bareel St-Gillis), tram tracks form a circle in the carriageway, while Churchill, Verboekhoven and Altitude Cent (Hoogte Honderd) have reserved tram tracks inside the roundabout. At Vanderkindere and Place Stéphanie (Stefaniaplein), they go straight through the centre, in the latter case with a slip track up the Chaussée de Charleroi (Charleroisesteenweg), while at Montgomery they tunnel underneath.

- In Dublin, Ireland, the Red Cow interchange at the N7/M50 junction is grade-separated and is signal-controlled with secondary lanes (separate from the main roundabout) for those making left turns. The junction, the busiest in Ireland, had tram lines added to it with the opening of the Luas system in 2004. The tracks pass across one carriageway of the N7, and across the southern M50 sliproads. Trams pass every five minutes at rush hour. The roundabout was replaced with a grade-separated free flowing junction.

- Gothenburg, Sweden has a tram roundabout at Mariaplan in the inner suburb of Majorna. The trams make a right turn, giving the roundabout an odd design.

- In Warsaw, trams typically cross straight through roundabouts and have junctions in the centre of them. In Wrocław, Poland, trams pass through the Powstańców Śląskich Roundabout, stopping in the roundabout (north-headed track).

- The Silesian tram network in Poland has two tram roundabouts. In the city centre of Katowice, the tram line passes through the centre of the Ziętka Roundabout in a north–south alignment, with a tram stop in the centre of the circle. In Będzin, unusually, the tram junction itself forms a circular roundabout, with trams going around the circle; there are tram stops immediately outside the roundabout on each branch.

- In Vítězné náměstí (Victory Square) in Prague, Czech Republic, a tramway crosses the carriage way of the roundabout at three places. Entering as well as leaving trams give way to vehicles. In the years 1932–42 trams circulated much like vehicles.

- In Kyiv, Ukraine an interchange of two "fast tram" lines is below a roundabout.

- Oslo, Norway also has many roundabouts with tram tracks passing through; for example at Bislett, Frogner plass, Sinsen, Solli plass, Carl Berners plass and Storo.

- In Wolverhampton, England, the West Midlands Metro tram passes through the centre of a roundabout on the approach to its terminus at St Georges. This also happens in New Addington in Croydon on the Tramlink north of King Henry's Drive tram stop on Old Lodge Lane at the junction to King Henry's Drive.

- In Sheffield, England the Sheffield Supertram systems crosses two major roundabouts. At the Brook Hill roundabout near Sheffield University, the tramway passes underneath the roundabout in a subway, while at Park Square in the city centre it travels above the roundabout on bridges and viaducts with a junction in the central island.

- A roundabout in southern Zagreb, Croatia features tram tracks passing through, curving at a 90° angle, as well as a full tram mini-roundabout inside the middle road island. In Croatia, where tram tracks enter the road without traffic lights, trams have the highest priority and other non-emergency vehicles are required to yield.

- In Salt Lake City, Utah a light rail line on the south side of the University of Utah crosses a roundabout where Guardsman Way meets South Campus Drive. Like virtually all rail crossings in the United States, both crossings in the circle are equipped with boom barriers.

- In Kassel, Germany, Lines 4 and 8 pass through the centre of the roundabout at Platz der Deutschen Einheit. The tram stops are in the centre of the roundabout. Roundabout traffic is controlled by traffic lights. Pedestrian access is via subway and street-level crossings at the lights.

- In Bremen, Germany, tram lines 8 and 6 pass through the centre of the roundabout "Am Stern" east of the main railway station. They enter from the west and exit in a northeastern direction, thus making a slight bend within the roundabout. Both stations are situated on the north-eastern edge of the roundabout. Traffic is controlled by two-colour traffic lights inside the roundabout.

Railways

In Jensen Beach, Florida, the main line of the Florida East Coast Railway running north–south bisects the two-lane roundabout at the junction of Jensen Beach Boulevard running east–west. It hosts three other roads and the service entrance to a large shopping plaza. Boom barriers line the railway crossings. The landscaped central island bisected by the tracks was originally curbed/kerbed, but 18-wheelers had trouble negotiating the roundabout, so the curbs were replaced with painted concrete strips. The roundabout was built in the early 2000s and improved traffic flow, although long freight trains often cause delays.

Two roundabouts in the Melbourne metropolitan area, Highett, Victoria and Hampton, have heavy rail crossing the roundabout and through the inner circle. Boom barriers protect the railway from oncoming traffic at the appropriate points in the roundabout.

At the Driescher Kreisel in Bergisch Gladbach, Germany, a railway serving a nearby paper factory crosses a roundabout located next to a shopping centre and pedestrian zone. The flow of traffic and pedestrians is governed by 14 barriers, 22 traffic lights and 8 loudspeakers. The barriers close three times daily for 7 minutes to allow trains to pass.

In New Zealand's South Island, two roundabouts join major roads where a railway cuts through. One is at the intersection between State Highway 1 (as Sinclair Street and Main Street from the east) and Main Street (from the west), Park Terrace and Redwood Street in the city of Blenheim. Here the Main North Line bisects the roundabout and separates Park Terrace and Main Street eastbound from the rest of the roundabout. The other roundabout is located at Kumara Junction on the West Coast, where the Hokitika Branch separates State Highway 6 southbound from SH 6 northbound and State Highway 73. Both roundabouts are controlled by flashing red lights, with additional boom barriers at the Blenheim roundabout.

Through roundabout

Also known as a hamburger roundabout, these junctions are signalised and have a straight-through section of carriageway for one of the major routes. The hamburger name derives from the fact that the plan view resembles the cross-section through a hamburger. The United Kingdom has examples on the A580 East Lancashire Road in St Helens, on Haydock Island in Merseyside (which also features the M6 passing overhead), and on the Astley/Boothstown border. More examples are the A6003 at Kettering, the A538 near Manchester Airport, the "Showcase" junction on A329 at Winnersh, Berkshire and the A63/A1079 Mytongate junction in Hull. Examples also exist in Bracknell, Hull, Bramcote in Nottinghamshire and Reading, as well as on the N2/M50 intersection in Dublin, Ireland. In Perth, Western Australia, one is found at the intersection of Alexander Drive, Morley Drive and The Strand. Throughabouts are very common in Spain, where they are called raquetas (Spanish for " racket") or glorieta/rotonda partida ("split roundabout").

-

Throughabout

Throughabout

-

Throughabout road sign in the Netherlands 51°51′02″N 5°49′54″E / 51.850517°N 5.831576°E / 51.850517; 5.831576

Throughabout road sign in the Netherlands 51°51′02″N 5°49′54″E / 51.850517°N 5.831576°E / 51.850517; 5.831576

-

Throughabout road sign in Australia 31°53′25″S 115°52′12″E / 31.8902952°S 115.8698988°E / -31.8902952; 115.8698988

Throughabout road sign in Australia 31°53′25″S 115°52′12″E / 31.8902952°S 115.8698988°E / -31.8902952; 115.8698988

Only bicycle-pedestrian roundabouts

The same features that make roundabouts attractive for roadway junctions led to their use at junctions of multi-use trails.

The University of California, Davis and Stanford University, as well as the Cape Cod and Old Colony rail trails have bicycle-pedestrian roundabouts. A roundabout along the Clear Creek Trail in Bloomington, Indiana, connects the main trail to its spur.

Roundabouts are used on off-road bicycle trails in Florida, Colorado, Alaska, and Wisconsin.

An elevated roundabout is located in Eindhoven, serving pedestrian and bicycle traffic only, above the main conventional roadway intersection. It is known as the Hovenring.

See also

For the at-grade intersection design analogous to dumbbell and dogbone interchanges, see Bowtie (road).- Complete streets

- Direction of traffic

- History of road transport

- History of street lighting in the United States

- History of roads in Ireland

- Level of service

- Leif Ourston, an early proponent of roundabouts in the United States

- Roundabout Appreciation Society

- Roundabout dog

- Traffic congestion

Notes

- There is also a branch line immediately north of the roundabout going west, and an additional tram stop on that branch.

References

- ^ The New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, Volume 2, Clarendon Press, Oxford (1993), page 2632

- ^ U.S. Department of Transportation 2013, para 1.5.

- ^ Ourston, Leif; Bared, Joe G. (1995). "Roundabouts: A Direct Way to Safer Highways". Public Roads. 59 (2). Federal Highway Administration: 41–49. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- "Roundabout Benefits". Washington State Department of Transportation. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- Hesch, Maxine. "Quantitatively Determining the Emissions Reduction Benefits of the Replacement of a Signalized Intersection by a Roundabout" (PDF). New York State Department of Transportation. Retrieved 6 October 2013.

- ^ "Roundabouts". IIHS-HLDI crash testing and highway safety.

- "Roundabout Rules of the Road". Archived from the original on 9 January 2014. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- P. M. Wolf, Eugene Henard and the Beginning of Urbanism in Paris, 1900–1914, International Federation for Housing and Planning, The Hague, 1969, cited by Ben Hamilton-Baillie and Phil Jones, Improving traffic behaviour and safety through urban design, Proceedings of ICE – Civil Engineering| volume=158 Issue 5 May 2005 p. 41 "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 July 2007. Retrieved 10 October 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Verhoeven, Dolly (red.) (2009). De Canon van Nijmegen. Nijmegen: Uitgeverij Vantilt. p. 131. ISBN 9789460040351.

- "Was alles in Görlitz erfunden wurde – Alles-Lausitz.de". Alles-Lausitz.de (in German). Archived from the original on 7 August 2017. Retrieved 5 June 2017.

- http://twofeet.weebly.com/walking-blog/the-five-circles-of-hanchett-park The Five Circles of Hanchett Park, 7 June 2014

- BBC News (2 November 2004). "Roundabout Magic". Retrieved 13 May 2007.

- Letchworth Garden City Heritage Foundation. "Sign of the Times". Archived from the original on 16 October 2006. Retrieved 14 December 2006.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering (4 December 2010). Roundabouts: An Informational Guide (2nd ed.). doi:10.17226/22914. ISBN 978-0-309-15511-3.

- ^ Christine Beldon (17 December 2019). "Why The U.S. Hates Roundabouts". Cheddar. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- "Frank Blackmore: traffic engineer and inventor of the mini-roundabout". The Times. London. 14 June 2008. Archived from the original on 24 May 2010. Retrieved 15 June 2008.

- Ourston Roundabout Engineering, Inc (13 January 2010). "Leif Ourston receives Frank Blackmore Award". Ourston.com. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- Clint Pumphrey. "How Roundabouts Work". howstuffworks.com

- "Roundabouts: A Direct Way to Safer Highways | FHWA". highways.dot.gov. Retrieved 15 September 2023.

- ^ Kooman, Bas (March 2001). "De rotonde. Veilig rondjes rijden?". Kampioen (in Dutch). 116 (3): 65–66.

- Hadley, Jane (22 November 2004). "Getting There: Perks for drivers of hybrid cars? Sorry, and here's why not". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. p. B1. Archived from the original on 22 November 2004. Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- Dahl, Doug (18 January 2021). "With a wink and a nod, a quick left often is drivers' go-to move at calming circles". The Bellingham Herald. Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ Tollazzi, Tomaž (2014). Alternative Types of Roundabouts: An Informational Guide. Cham: Springer. p. 110. ISBN 9783319090849. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ Keh, Andreh (18 November 2010). "European Import Has Cars Spinning. Heads, Too". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- Wylie, Ian (19 October 2015). "'Traffic lights are so dictatorial' ... but are roundabouts on the way out?". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- Wright, Lucas (18 September 2019). "Highlighting the first modern roundabouts in the country during National Roundabout Week". KLAS. Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- Roselli, Dayna (18 April 2007). "Roundabouts". lasvegasnow.com. Archived from the original on 26 March 2012. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- ^ Tom Geoghegan (1 July 2011). "Is the British roundabout conquering the US?". BBC website. Retrieved 1 July 2011.

- "Modern Roundabout Practice in the United States" (PDF).

- Retting, Richard A.; Kyrychenko, Sergey Y.; McCartt, Anne T. (2007). "Long-Term Trends in Public Opinion Following Construction of Roundabouts". Journal of the Transportation Research Board. 2019: 219–224. doi:10.3141/2019-26. S2CID 110914100.

- "WSDOT – Washington's Roundabouts". 11 October 2016. Archived from the original on 11 October 2016. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

-

"Roundabouts: an informational guide" (PDF). Turner-Fairbank Highway Research Center. 16 November 2017. Archived from the original on 12 January 2009. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "What lane should I use on a roundabout?". AXA.ie. AXA. 16 November 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- "New Jersey roundabouts" (PDF).

- Capuzzo, Jill P. (25 November 2007). "A Shift, but for Some Drivers, a Vicious Circle". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- "Drum Hill Rotary" (Map). Google Maps.

- "Roundabout opens in north Japan after lesson learned from 2011 quake, tsunami". Mainichi Daily News. 6 January 2020. Retrieved 20 November 2023.

- American Heritage Archived 26 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine ("roundabout: Chiefly British A traffic circle."), Random House ("roundabout: Chiefly Brit. See traffic circle."), Merriam-Webster("roundabout, noun: British: rotary 2"; "rotary 2: a road junction formed around a central circle about which traffic moves in one direction only—called also circle, traffic circle)Macmillan "roundabout: a circular area where three or more roads meet that you have to drive around in one direction in order to get onto another road. The American word is traffic circle or rotary.", ("roundabout: UK (US traffic circle)), Concise Oxford (rotary: N. Amer. a traffic roundabout.)

- "Safety Aspects of Roundabouts – FHWA Safety Program". 3 September 2014. Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- "General Law – Part I, Title XIV, Chapter 89, Section 8". malegislature.gov. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- "Rhode Island Driver's Manual" (PDF). Dmv.ri.gov. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- "Scottish words of the week: The Dundee dialect". www.scotsman.com. 4 October 2013. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- "Revealed: What is the most dangerous roundabout in Birmingham?". www.birminghammail.co.uk. 26 August 2016. Retrieved 15 September 2023.

- Jersey, States of. "Government of Jersey". gov.je.

- Intersection Safety Roundabouts – Safety – Federal Highway Administration. February 2010. Archived from the original on 17 April 2010. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- Kittleson & Associates. "Kansas Roundabout Guide: A Supplement to FHWA's Roundabouts: An Informational Guide" (PDF). Kansas Department of Transportation. Retrieved 26 August 2009.

- "Driver manual" (PDF). Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Registry of Motor Vehicles. "Sharing the Road: A User's Manual for Public Ways". Retrieved 13 May 2009.

- "Vehicle & Traffic Law – Right of Way". 3 July 2011. Archived from the original on 3 July 2011. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- ^ "Index – Roundabout: An Informational Guide, June 2000 – FHWA-RD-00-067". Fhwa.dot.gov. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- TSM https://en.wikisource.org/Traffic_Signs_Manual/Chapter_5/2009/8

- Shashi S. Nambisan, Venu Parimi (March 2007). "A Comparative Evaluation of the Safety Performance of Roundabouts and Traditional Intersection Controls". Institute of Transportation Engineers. Retrieved 27 November 2007.

- Underlien Jensen, Søren (November 2012). "Rundkørsler og trafiksikkerhed" (PDF). Trafik & Veje (in Danish): 26–29.

- sep 2020, Clock 20; Journalist, kl 09:01 Bemærk: Artiklen er mere end 30 dage gammel Sebastian Myrup Hansen. "Renovering af omdiskuteret rundkørsel er i gang - ikke godt nok mener kørelærer". TV 2 Lorry (in Danish). Retrieved 27 January 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Hansen, Winnie (2 June 2019). "Spørg Fagfolket: Hvorfor skal øen i midten af rundkørslen være så høj?". Ingeniøren (in Danish). Vejdirektoratet.

analysis of 332 roundabouts. It was very clear that if the height in the middle of the roundabout was over two meters, then it was much safer than other designs. The accident rate was significantly lower in the high roundabouts

- "Art In Public Places, Bend, Oregon". Art in Public Places. Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- "Pillar of art" (PDF). Art in Public Places. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- "Fuerteventura, art on the roads: roundabouts as galleries". Roberto Alborghetti. 2 July 2012. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- "Photographs of French roundabouts" (Map). Google Maps.

- ^ "Roundabout photographs from The Netherlands, Belgium, Germany and Austria" (Map). Google Maps.

- "Roundabout photographs from Italy" (Map). Google Maps.

- "Roundabout photographs from Spain" (Map). Google Maps.

- ^ "Unusual road roundabouts: artistic, and otherwise. A collection of more than 2000 photographs, by almost 200 amateur photographers, from all over the world". Panoramio: Roundabouts. www.panoramio.com. Archived from the original on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- "Roundabout / Kreisverkehr – streets with a roundabout / Straßen mit einem Kreisverkehr". Flickr (in English and German). www.flickr.com. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- "Inventory of French roundabouts" (in French). Marc Lescuyer. Archived from the original on 11 November 2008. Retrieved 1 January 2010.

- "Section 7: Laws and Rules of the Road". California DMV.

- "Facts & figures". swov.nl.

- ^ "Modern Roundabouts, an Informational Guide". Federal Highway Administration Research and Technology. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- "FHWA - MUTCD - 2003 Edition Chapter 3B2". Federal Highway Administration (FHWA).

- R. Schnüll, J. Lange, I. Fabian, M. Kölle, F. Schütte, D. Alrutz, H.W. Fechtel, J. Stellmacher-Hein, T. Brückner, H. Meyhöfer: Sicherung von Radfahrern an städtischen Knotenpunkten , Bericht der Bundesanstalt für Straßenwesen zum Forschungsprojekt 8952, 1992

- Vortragsfolien Radverkehr Scroll to the section labelled "Kreisverkehr". A translation of the text reads: Graphic from Sicherung von Radfahrern an städtischen Knotenpunkten , (BASt, 1992). Accident numbers in large circular junctions with different bicycle facilities show: 1. Why there should be no pathways or bike lanes at these junctions; 2. Even when cyclists use the roadway, their risk is relatively high at these junctions.

- Maycock, G., and Hall, R. D. (1984). "Accidents at 4-Arm Roundabouts." TRRL1120, Transport and Road Research Laboratory (TRRL), Crowthorne, England.

- "Roundabouts | ADOT". azdot.gov.

- ^ Design manual for bicycle traffic. Rik de Groot, vervoer en infrastructuur CROW kenniscentrum voor verkeer. Ede, The Netherlands. 2016. pp. 147–148. ISBN 978-90-6628-659-7. OCLC 972096448.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - "UK's first Dutch-style roundabout welcomed by road safety campaigners - Highways Industry". Highways Industry. 7 August 2020. Retrieved 29 July 2024.

- "Ireland's first Dutch-style roundabout opened in Dublin 15 -". IrishCycle.com. 29 May 2023. Retrieved 29 July 2024.

- Taylor, M.P., Barton, E.V., Bliss, J. and O'Brien, A.P. (1993). Effectiveness Audit of ARRB Intersection Capacity Research. Research Report ARR 242. ARRB Transport Research Ltd, Vermont South, Australia. Archived from the original on 27 February 2016.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - TRB (2016). Highway Capacity Manual, Sixth Edition: A Guide for Multimodal Mobility Analysis. Transportation Research Board, National Research Council, Washington, DC, US.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - TRB (2010). Roundabouts: An Informational Guide. NCHRP Report 672. Transportation Research Board, National Research Council, Washington, D.C., US, in cooperation with US Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration. doi:10.17226/22914. ISBN 978-0-309-15511-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Pochowski, Alek; Paul, Andy; Rodegerdts, Lee A. (2016). Roundabout Practice, A Synthesis of Highway Practice. National Cooperative Highway Research Program, NCHRP SYNTHESIS 488. Washington DC, US.: Transportation Research Board. doi:10.17226/23477. ISBN 978-0-309-27208-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Nambisan, Shashi S.; Parimi, Venu (March 2007). "A Comparative Evaluation of the Safety Performance of Roundabouts and Traditional Intersection Controls". Institute of Transportation Engineers.

- "Status Report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- Richtmeyer, Richard (6 January 2008). "Safer Roundabouts Sprouting Up All Over New York, Nation". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 15 December 2012. Retrieved 10 January 2008.

- "Roundabouts - Topic overview". Insurance Institute for Highway Safety.

- Wijnands, J.S.; Zhao, H.; Nice, K.A.; Thompson, J.; Scully, K.; Guo, J.; Stevenson, M. (2020). "Identifying safe intersection design through unsupervised feature extraction from satellite imagery". Computer-Aided Civil and Infrastructure Engineering. 36 (3): 346–361. arXiv:2010.15343. doi:10.1111/mice.12623. S2CID 225103031. PDF

- Wilke, A. and Koorey, G. (2001). How Safe are Roundabouts for Cyclists? In TranSafe Issue 5, April 2001. Wellington, NZ. PDF Archived 15 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- "Crash analysis system". Retrieved 29 November 2007.

- Campbell, D., Jurisich, I., Dunn, R. 2006. Improved multi-lane roundabout designs for cyclists. Land Transport New Zealand Research Report 287. 140 pp. PDF

- Pedestrian Access to Modern Roundabouts: Design and Operational Issues for Pedestrians who are Blind retrieved 6/26/2010 access-board.gov Archived 31 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Bill Baranowski, P.E., Pedestrian Crosswalk Signals at Roundabouts: Where are they Applicable?

- "| Guinness World Records".

- "History of Roundabouts". Archived from the original on 27 January 2008. Retrieved 29 November 2007.

- Transport for London https://tfl.gov.uk/info-for/media/press-releases/2014/november/tottenham-hale-improvement-works-complete

- Rhodes, Belinda (21 June 2008). "Frank Blackmore Determined, maverick traffic engineer who invented the mini-roundabout". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- "The Highway Code – Roundabouts". Retrieved 14 May 2009. Section 188, referring to Road Traffic Act 1988, Section 36, and Traffic Signs Regulations & General Directions 2002, Regulations 10(1) & 16(1)

- "Turborotonde en turboplein: ontwerp, capaciteit en veiligheid" [Turbo Roundabout and Turbo Circle; Design, Capacity and Safety] (in Dutch). Delft University of Technology. 8 January 2013. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- "Turborotondes - CROW". Archived from the original on 26 September 2017. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- "Benefits of Turboroundabouts". Transoft Solutions Inc. 2014. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ^ Vos, Christiaan (31 January 2016). "Effecten realisatie turborotonde onderzocht" [Effects research of turbo roundabouts]. Verkeer – Verkeersveiligheid – Vorm (Traffic, Safety, Form) (in Dutch). Dirk de Baan. Archived from the original on 28 January 2017. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- Isaak Yperman; Ben Immers (2003). "Capacity of a turbo-roundabout determined by micro-simulation". Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Department of Civil Engineering – Transportation Planning and Highway Engineering. Archived from the original (pdf) on 27 December 2016. Alt URL

- "Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices for Streets and Highways – Part 3: Markings" (PDF). U.S. Department of Transportation – Federal Highway Administration. 2003.

- For sources and references see the separate article on this tunnel and its roundabout.

- "Video: Eerste rit over het nieuwe knooppunt Joure". Leeuwarder Courant. 13 October 2017.

- UK Department for Transport, Signal Controlled Roundabouts LTN 1/09

- Ibanez, Guillermo (2020). "Synchronous Roundabouts with Rotating Priority Sectors (SYROPS): High Capacity and Safety for Conventional and Autonomous Vehicles". Electronics. 9 (10): 1726. doi:10.3390/electronics9101726. hdl:10017/44928.

- "Frank Blackmore: traffic engineer and inventor of the mini-roundabout". The Times. London. 14 June 2008. Archived from the original on 24 May 2010. Retrieved 15 June 2008.

- Swindon's Magic Roundabout from the air, retrieved 23 March 2022

- Brits vote on the best and worst roundabouts, Easier.com. 20 December 2005, retrieved 18 January 2008

- "World's worst junctions revealed". Auto Express.

- 10 Scariest Junctions in the UK, BBC, 27 November 2009.

- "High Wycombe" (Map). Google Maps.

- "Hatton Cross" (Map). Google Maps.

- "SABRE: Magic Gyratory". 8 November 2013. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 October 2019. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Vítězné náměstí, Prague trams fun web

- "Roundabout" (Map). Google Maps. Retrieved 15 January 2012.

- "Jensen Beach Roundabouts Charrette". Archived from the original on 21 November 2008. Retrieved 16 October 2007.

- "145.039044269836,-37.9447586507931". Australia Mapsearch.

- "144.9930580000&,-37.9200150000". Australia Mapsearch.

- "Der Driescher Kreisel". Archived from the original on 27 September 2011.

- "Blenheim Roundabout" (Map). Google Maps. Retrieved 15 January 2012.

- "Kumara Junction Roundabout" (Map). Google Maps. Retrieved 15 January 2012.