Cuerda seca (Spanish for "dry cord") is a technique used when applying coloured glazes to ceramic surfaces.

Description

When different coloured glazes are applied to a ceramic surface, the glazes have a tendency to run together during the firing process. In the cuerda seca technique, the water-soluble glazes are separated on the surface by thin lines of a greasy substance to prevent them running out of their delineated areas. A dark pigment such as manganese carbonate is usually mixed with the grease to produce a dark line around each coloured area.

History

The origin of the technique is not known for certain. Many scholars believe that the cuerda seca technique originated primarily in al-Andalus (Islamic Spain and Portugal) in the second half of the 10th century, during the Umayyad period (citing Umayyad-era examples from Suza). Scholar Juan Zozaya argues that the advent of this style in al-Andalus could have been spurred by Chinese ceramics which were imported to the region from an early period. The technique was further advanced during the Taifas period in the 11th century. Preserved fragments of tiles from the late 12th-century minaret of the Kasbah Mosque in Marrakesh, Morocco, have been cited as the earliest surviving example of cuerda seca tilework being used for architectural decoration.

In Central Asia, tiles were manufactured using the cuerda seca technique from the second half of the 14th century. Hans Van Lemmen postulates that these tiles, from the Timurid period (late 14th to 15th centuries), were "earliest development of cuerda seca". The introduction of different coloured glazes is recorded in the mausoleums of the Shah-i-Zinda necropolis in Samarkand. In the 1360s the colours were restricted to white, turquoise and cobalt blue but by 1386 the palette had been expanded to include yellow, light-green and unglazed red. Large quantities of cuerda seca tiles were produced during the Timurid (1370–1507) and Safavid (1501–1736) periods.

In the 15th century Persian potters from Tabriz introduced the technique into Turkey and were responsible for decorating the Yeşil Mosque in Bursa (1419-1424). Within the Ottoman Empire cuerda seca tilework fell out of fashion in the 1550s and new imperial buildings were decorated with underglaze-painted tiles from İznik. The last building in Istanbul to include cuerda seca tilework was the Kara Ahmed Pasha Mosque which was designed in 1555 but only completed in 1572.

Gallery

-

Pitcher in cuerda seca style from Susa in Iran, 8th-9th century

Pitcher in cuerda seca style from Susa in Iran, 8th-9th century

-

Cuerda seca tile from the Alcazar of Seville, 12th-13th century

-

Tiles in the Green Mosque, Bursa, c. 1420

Tiles in the Green Mosque, Bursa, c. 1420

-

Details of the Green Tomb in Bursa

Details of the Green Tomb in Bursa

-

Tile from Khargird in Iran, mid 15th century

Tile from Khargird in Iran, mid 15th century

-

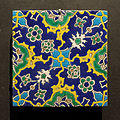

Ottoman tile, Istanbul, first half 16th century

Ottoman tile, Istanbul, first half 16th century

-

Dish from Seville in Spain, early 16th century

Dish from Seville in Spain, early 16th century

Notes

- Campbell 2006.

- Soustiel, Jean (1985). La céramique islamique : le guide du connaisseur. Fribourg: Office du livre. ISBN 271910213X.

- ^ Pérez-Arantegui, Josefina; Soto, Mercedes; Castillo, Juan Ramon (1999). "Examination of the cuerda seca decoration technique on Islamic ceramics from al-Andalus (Spain)". Journal of Archaeological Science. 26 (8): 935–941. Bibcode:1999JArSc..26..935P. doi:10.1006/jasc.1999.0400.

- Chapoulie, R.; Delery, C.; Daniel, F.; Vendrell-Saz, M. (2005). "Cuerda seca ceramics from al-Andalus, Islamic Spain and Portugal (10th−12th centuries AD): investigation with SEM–EDX and cathodoluminescence". Archaeometry. 47 (3): 519–534. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4754.2005.00217.x.

- ^ Lintz, Yannick; Déléry, Claire; Tuil Leonetti, Bulle (2014). Le Maroc médiéval: Un empire de l'Afrique à l'Espagne. Paris: Louvre éditions. p. 332. ISBN 9782350314907.

- Zozaya, Juan (2016). "Eastern Influences in al-Andalus". In Marin, Manuela (ed.). The Formation of al-Andalus, Part 1: History and Society. Routledge. p. 463. ISBN 978-1-351-88961-2.

- Porter 1995, p. 18.

- Lemmen, Hans Van (2013-10-22). 5000 Years of Tiles. Smithsonian Institution. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-58834-398-7.

- Atasoy & Raby 1989, p. 373, fn 23.

- Porter 1995, p. 20.

- Atasoy & Raby 1989, p. 83.

- Atasoy & Raby 1989, p. 220.

- Necipoğlu 2005, pp. 377–384.

Sources

- Atasoy, Nurhan; Raby, Julian (1989). Iznik: The Pottery of Ottoman Turkey. London: Alexandra Press. ISBN 978-1-85669-054-6.

- Campbell, Gordon, ed. (2006). "Cuerda seca and cuenca tiles". The Grove Encyclopedia of Decorative Arts, Volume 1. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 293. ISBN 978-0-19-518948-3.

- Necipoğlu, Gülru (2005). The Age of Sinan: Architectural Culture in the Ottoman Empire. London: Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-86189-253-9.

- Porter, Venetia (1995). Islamic Tiles. London: British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-7141-1456-9.

Further reading

- Valdés Fernández, Fernando; Casamar Pérez, Manuel (1984). "Origen y desarrollo de la técnica de cuerda seca en al Península Ibérica y en el Norte de Africa durante el siglo XI". Al-qantara: Revista de estudios árabes. 5 (1): 383–404. ISSN 0211-3589.

- Gestoso y Pérez, José (1899). Ensayo de un diccionario de los artífices que florecieron en Sevilla : desde el siglo XIII al XVIII inclusive. Volume 1 (in Spanish). Seville: En la oficina de la Andalucía moderna. p. 77. OCLC 9986104.

External links

- The cuerda seca method, Qantara project.